Pauses in CDC Vaccine Data Raise Concerns for Measles Surveillance

CDC Vaccine Databases Stop Updating

In 2025, dozens of public health databases on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website stopped updating on schedule. Most of the paused databases tracked vaccines or vaccine-preventable diseases. The pauses were not explained on the pages themselves, and many of the datasets had not been updated for months.

Why Measles Surveillance Depends on Timely Data

The gaps are especially significant for diseases like measles. Measles is one of the most contagious viruses known, but it is preventable with vaccination. Controlling measles depends on timely data showing where cases are occurring, where vaccination rates are declining, and where outbreaks may be emerging. When vaccine surveillance data are delayed or missing, it becomes harder for public health officials, clinicians, and communities to respond quickly.

What the Audit Found

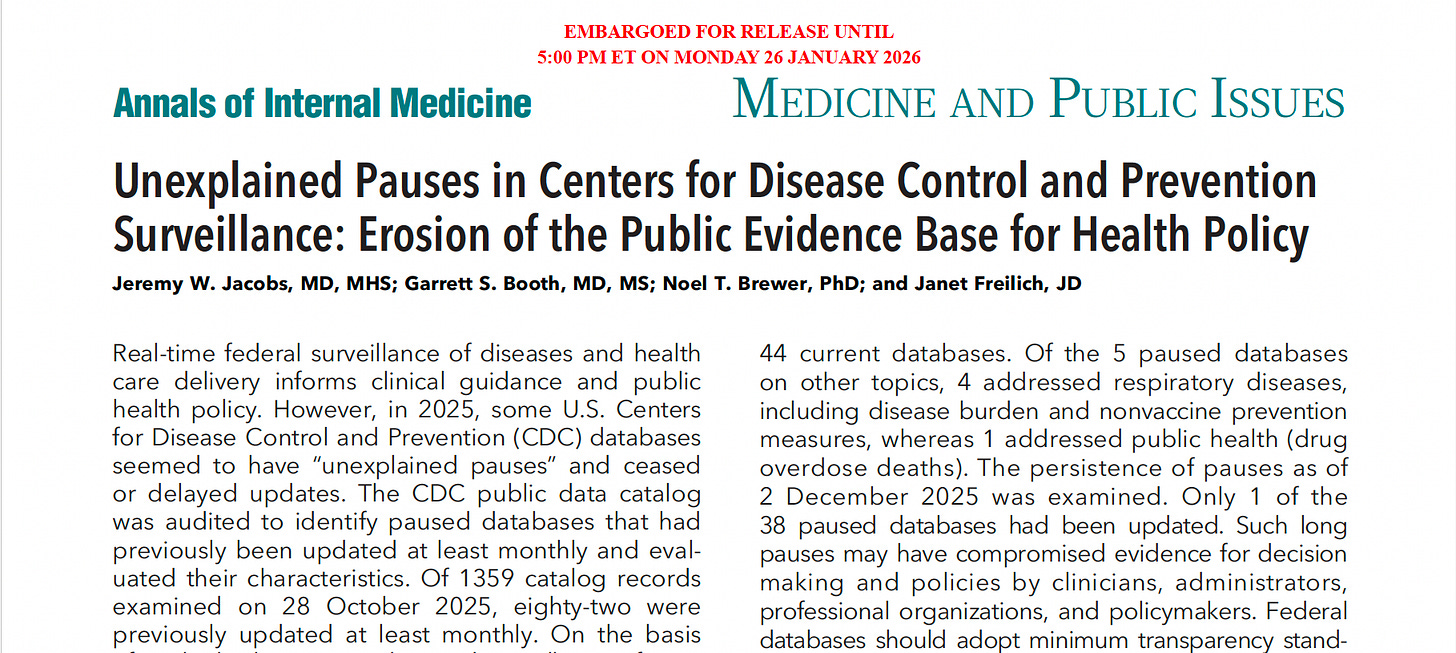

An audit published in Annals of Internal Medicine found that 38 of 82 CDC databases expected to update at least monthly had unexplained pauses. Nearly 90% of the paused databases focused on vaccination or vaccine-preventable diseases. Most had not been updated for more than six months, and only one resumed updates by early December 2025. The authors warned that these gaps weaken decision-making and public trust.

Expert Warning on Data Interruptions

In an accompanying editorial, Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, MPH, CEO of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, warned that “interruptions in CDC data reporting undermine our ability to recognize outbreaks and respond rapidly.” She has also stressed that clinicians and the public rely on CDC websites for guidance on vaccines, travel, prevention, and treatment, and that unexplained gaps create uncertainty at a time when accurate information is critical.

Why Measles Remains a Risk

Measles illustrates why current data matter. The virus spreads through the air and can remain infectious in a room after an infected person leaves. One person with measles can infect 12 to 18 unvaccinated people nearby. Preventing outbreaks requires about 95% of a community to receive two doses of the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine. Surveillance data help identify when vaccination coverage falls below that threshold. (This is the kind of data, by the way, that enabled the eradication of smallpox.)

The CDC’s measles surveillance systems typically track cases, outbreaks, and vaccination coverage across states and communities. These data guide public health responses, including where to focus outreach, vaccination clinics, and public alerts. They also help clinicians recognize patterns and respond more quickly. When updates pause, early warning signs may be missed.

The audit did not determine why the pauses occurred, but emphasized that the lack of transparency is a concern in itself. Public health officials note that the issue is not theoretical: the United States has continued to report measles cases and outbreaks in recent years, often linked to under-vaccinated communities.

What This Means for Parents and Schools

For parents, delayed measles and vaccine data can make it harder to assess risk. Families often use CDC information to decide when to update vaccinations, how cautious to be about travel, or how seriously to take reports of local measles cases. When data are out of date, parents may not learn about community spread until schools or health departments issue alerts.

Schools also rely on this information. Measles spreads easily in classrooms, cafeterias, and school buses, particularly among children who are unvaccinated or too young to be fully vaccinated. Timely surveillance data help schools prepare for outbreaks, follow exclusion policies, and coordinate with health officials on vaccination efforts. Delays can reduce the time available to prevent wider spread.

As measles continues to reappear in parts of the United States, public health officials say restoring regular, transparent CDC vaccine surveillance is essential to detecting outbreaks early and preventing a disease long considered controllable from regaining ground.