On NPR: dot Gov ’26: The Department of Health and Human Services

Changes at HHS and at the CDC

https://the1a.org/segments/dot-gov-26-the-department-of-health-and-human-services/

Highlights

Who supports changes to the childhood vaccine schedule and why

Level-setting what vaccines are for (infection vs severe disease)

Significance of the vaccine schedule changes

Jenn White: Dr. Gounder, the vaccines moved from being routinely recommended to being in a category based on risk factors include those for RSV, hepatitis A and B, and dengue. A third category that includes the flu shot and COVID vaccines is left up for parents to decide.

From your perspective, how significant are these changes—not just for families, but also for the medical community trying to figure out how best to advise patients?

Dr. Céline Gounder: … HHS has fundamentally changed U.S. childhood vaccine policy. And I have to emphasize: this is not because of any new safety or efficacy evidence. The existing vaccines remain safe and effective.

These changes were made to expand, quote, “parental choice,” and to align the U.S. schedule with very specific high-income countries—like Denmark, for example.

That comparison is really an apples-to-oranges argument because those countries have universal health care. They have national registries for diseases and immunizations. They have paid sick leave and family medical leave and easier access to affordable care.

One of the biggest concerns right now in this country—after grocery and food affordability—is health care affordability. The U.S. is far more unequal and has far greater barriers to appointments and the cost of care.

If you really wanted to compare the U.S. to equivalent countries—large, unequal countries without universal coverage—Denmark isn’t the right peer. Our peer countries would be Chile, Saudi Arabia, Poland, Turkey, Brazil. Those are countries that still recommend all of those vaccines that were taken off the universal list.

Quite frankly, the U.S. is essentially two countries: we are the most high-income developed country in the world, and we’re also a developing country at the same time.

And trying to formulate guidance for our public health system that ignores the vast majority of people who live in low-income settings without access to care is really leaving most of the population behind.

What ACIP does and why it matters

Jenn White: Back in June, Secretary Kennedy dismissed all 17 members of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, or ACIP—that’s the agency’s vaccine advisory panel. In a statement, he said: “A clean sweep is necessary to reestablish public confidence in vaccine science.”

The panel was replaced by 11 new members in June selected by Kennedy.

Dr. Gounder, tell us more about the function this panel serves and how they’re usually appointed.

Dr. Céline Gounder: ACIP is an expert panel where you have to apply to be a member. They review your credentials—your scientific publications, your clinical experience, your standing in the field.

ACIP reviews the evidence—what’s come out since the last meeting on a particular vaccine or infectious disease—and they make recommendations that shape the U.S. vaccine schedule. Those recommendations need to be signed off by the CDC director.

They’re not technically binding. These are not vaccine mandates. But they matter because insurers and federal programs like the Vaccines for Children program rely on these recommendations to decide what they’re going to cover.

Over the summer, Secretary Kennedy fired all of the previous vetted members of the vaccine advisory committee and replaced them with people who are known to be vaccine skeptics.

Kennedy has complained that the committee in the past has rubber-stamped what CDC directors wanted. That’s not been the case. What we’re seeing now is the reverse: a committee rubber-stamping what a non-expert, nonclinician, nonscientist who has never taken care of patients wants of the vaccine schedule.

Who supports these changes to the vaccine schedule and why

Jenn White: Dr. Gounder, where are we seeing support for these changes around vaccines specifically?

Dr. Céline Gounder: Over the course of the pandemic in particular, we’ve seen the rise of a parental rights movement. Some of this was around COVID. We’ve also seen it around trans rights and gender-affirming care.

I think that’s where a lot of this is coming from: people wanting to take back agency, autonomy, and decision-making—whether or not they have full access to information in making those decisions.

Fundamentally, that is an ideological or political perspective. It is not about what is scientifically or best for public health.

CDC leadership vacuum

Jenn White: I want to talk about some of the top staff who have departed HHS in the last year. …

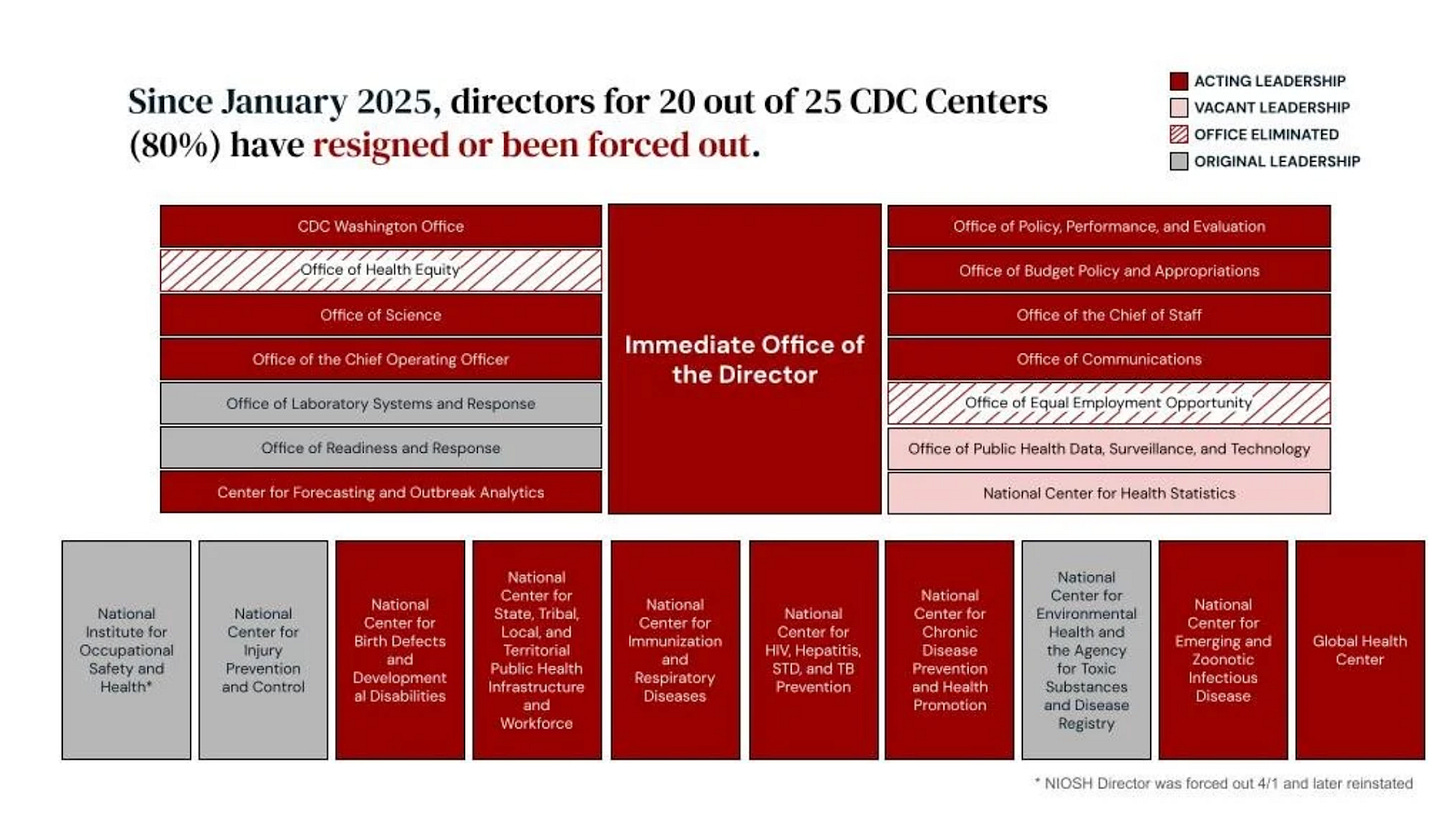

Lena Sun: … At CDC, 20 out of 25 top leaders across the agency—those positions are now vacant. You have a hollowing-out of expertise. It’s not just those four people.

Jenn White: Twenty out of 25.

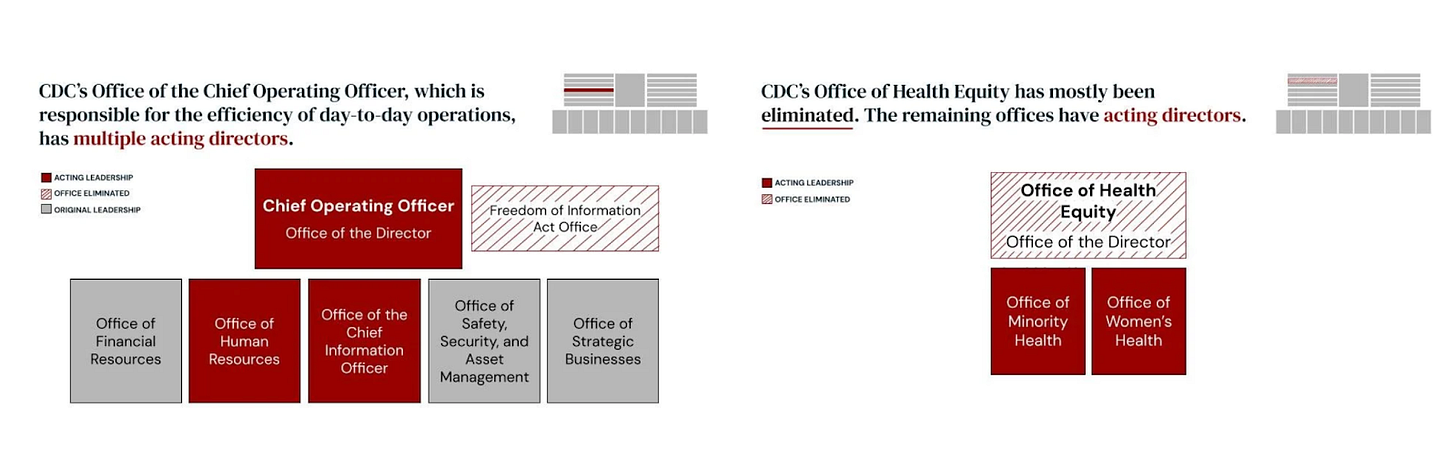

Dr. Céline Gounder: … To make it more concrete: where we have acting or vacant leadership includes the heads of the Center for Chronic Disease Prevention, the Center for HIV, Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, the Immunization Services Division, the Center for Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, the Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, the Global Health Center, the Office of Science—the list goes on.

This is an agency that has been so gutted that they were not able to respond to a lead crisis in Milwaukee schools. There’s now an HIV and hepatitis C outbreak outside Bangor, Maine, and the CDC refused to assist the state of Maine with that outbreak. This is where we are with public health today.

Flu vaccine effectiveness

Jenn White: One listener writes: “I am pro-vaccine. I and my adult children are fully vaccinated. I am an RN. However, I do have concerns about two vaccines. According to the CDC, the flu vaccine was only 38% effective on average over the past 20 years.”

And we should note: that 38% figure comes from effectiveness in 2017, and it was 39% in 2020, according to the NIH.

The listener goes on: “It does have possible serious side effects. Wearing a mask is more effective than a flu shot. Many of the patients I take care of who are in the hospital for flu have had flu shots.”

Dr. Gounder, I’d love to hear your response.

Dr. Céline Gounder: …with respect to the flu vaccine: vaccine effectiveness numbers need to be looked at carefully. Are you talking about prevention of infection, hospitalization, or death?

These vaccines are not perfect, but even reducing hospitalizations and deaths by 40% is a huge win.

As someone who works in the hospital during big flu spikes over the holidays—when you’re short-staffed and have many more patients coming in—cutting admissions by 40% matters.

Second: masks work as well as you wear them. One thing we learned during the COVID pandemic is that masks work. I did not get COVID the entire first year of 2020, wearing a mask at Bellevue Hospital taking care of COVID patients, because I wore it correctly.

But many people don’t want to wear masks. They don’t wear them correctly—they don’t cover their nose and mouth, or they don’t wear them tightly.

So masking is an alternative for people who don’t want to get vaccinated, but most people don’t want to be doing that outside of an emergency situation.

Level-setting what vaccines are for (infection vs severe disease)

Jenn White: Dr. Gounder, I also think this is a good time to level-set what vaccines actually do. Since COVID, there’s been misunderstanding about the degree to which vaccines prevent you from contracting an illness, rather than prevent severe illness.

Can you explain that?

Dr. Céline Gounder: The primary goal of vaccination is to reduce severe disease, hospitalization, and death.

I think people got confused early in 2021 because vaccine effectiveness against infection—soon after COVID vaccination—was close to 100%. But immunity wanes in terms of preventing infection.

By July, we had the outbreak in Provincetown, which showed protection against infection was starting to wane. But none of those people ended up in the hospital. That was a win, and it wasn’t communicated well.

If you look at other vaccines, some can protect against infection very well—measles is a great example. That’s because the incubation period—the time from exposure until illness—is much longer for measles than for flu or COVID.

That gives the immune system time to kick in and block infection. With flu and COVID, the infection progresses too quickly to block it completely. But the goal is still: don’t end up in the hospital.

If you take a baby with RSV, for many parents, not having to take their baby to the ICU would be a win. It’s not just whether the baby lives or dies. It’s the stress of hospitalization. You have to look at the key outcome we care about for each condition.

NIH funding

Jenn White: We got a statement from an HHS spokesperson about funding:

NIH is committed to restoring the agency to its tradition of upholding gold-standard evidence-based science. As we make America healthy again, NIH is carefully reviewing all programs to assure NIH is addressing the United States chronic disease epidemic. NIH and HHS are taking actions to prioritize research that directly affects the health of all Americans.

Dr. Gounder, what’s your response?

Dr. Céline Gounder: … In the past, awarding NIH grants was a meritocracy. It’s no longer a meritocracy—which is ironic for an administration that says it wants to fund the most meritorious science. This has become political, and it’s about political priorities.

It’s also about self-dealing. Matt Memoli, who served as acting NIH director for a period of time, directed half a billion dollars, with a B, or $500 million to himself and his colleague, Jeff Taubenberger, to do research on outdated influenza vaccines.

This is why Jeanne Marrazzo — who was briefly the successor to Tony Fauci — filed a whistleblower complaint and was fired.

So this is a politically motivated and self-dealing NIH and HHS when it comes to medical research funding.

Hepatitis B vaccine for newborns

Jenn White: Mark asks: “Why would you give an infant a hepatitis B shot? If a woman is being screened throughout her pregnancy, why not test the woman to see if she has hep B?”

Anne also writes: “Most pregnant women are tested for hep B. If a pregnant woman is negative, isn’t it almost impossible for her newborn infant to be born with hep B?”

Dr. Gounder, we have to let you go in a moment, but how would you respond?

Dr. Céline Gounder: First, many women do not get prenatal care, so they’re not getting tested. Even if they have hepatitis B, they may not know.

Second, hepatitis B is not only transmitted through sexual contact or injection drug use. That is a myth. A significant proportion is transmitted from caregivers who are not the mother—grandparents, or someone working in daycare.

Hepatitis B is far more infectious than HIV or hepatitis C, so more minimal exposures can lead to transmission.

Do you test everyone in your household? Do you test everyone at daycare? You don’t.

And we did this experiment 30 years ago. We know there are still infections in infants that can be prevented, which is why the recommendations changed over time.