HHS Overhaul Marks Major Shift in U.S. Childhood Vaccine Policy

January 6, 2026

Here’s a quick summary. More details below.

The U.S. government has enacted its most sweeping overhaul of childhood vaccination policy in more than half a century, reshaping both which vaccines are recommended for children and how those decisions are made.

The change was not driven by new safety concerns or scientific findings. Existing childhood vaccines are safe and effective. Senior officials say the goal is to give parents more choice and to align U.S. recommendations with those of other high-income nations.

What changed?

For decades, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) maintained a single national childhood vaccination schedule. This schedule shaped state school-entry requirements and supported access through the federally-funded Vaccines for Children (VfC) program, which provides free vaccines to eligible children.

That list has been replaced by a new three-tiered system:

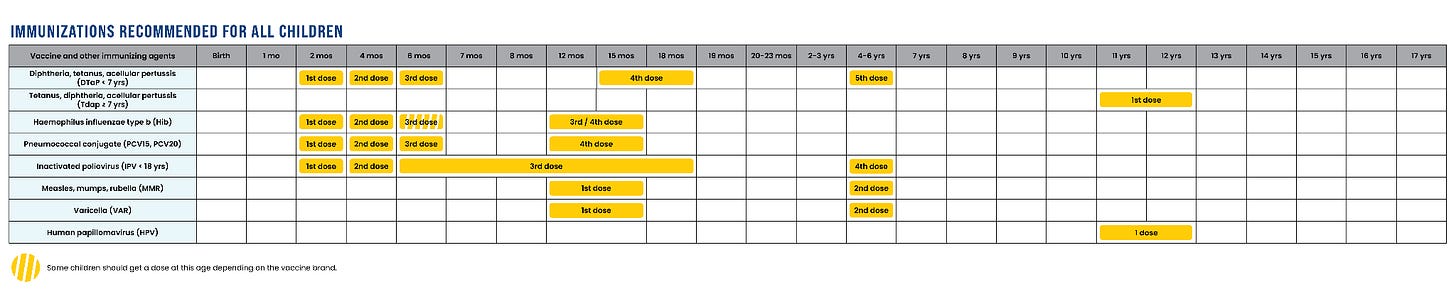

Universal vaccines: recommended for every child.

Vaccines for high-risk infants and children: for those with specific health conditions or elevated exposure risk.

Vaccines provided through “shared clinical decision-making”: chosen jointly by families and clinicians. This category means that access to these vaccines hasn’t been taken away, but it does mean that clinicians may not automatically offer these vaccines to all children. Families may need to request these vaccines.

Childhood vaccines against the following infections remain on the “must-get” list:

Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR)

Polio

Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis (whooping cough)

Haemophilus influenzae B

Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcal disease)

Varicella (chickenpox)

Human papillomavirus (HPV)

Immunizations HHS recommends for all children:

The vaccines that were moved off the universal list include:

Hepatitis A and B

Influenza (flu)

COVID

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

Rotavirus

Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcal disease)

However, these shots are still available and covered by insurance.

The new childhood vaccine recommendations are really confusing.

If you’re having trouble deciphering the new recommendations, you’re not alone. I couldn’t cover it all in 2 minutes and 30 seconds on air. And if I can’t explain all of this to you in a quick soundbite and easy to read graphics, a lot of people, including doctors, are going to be confused about what to do.

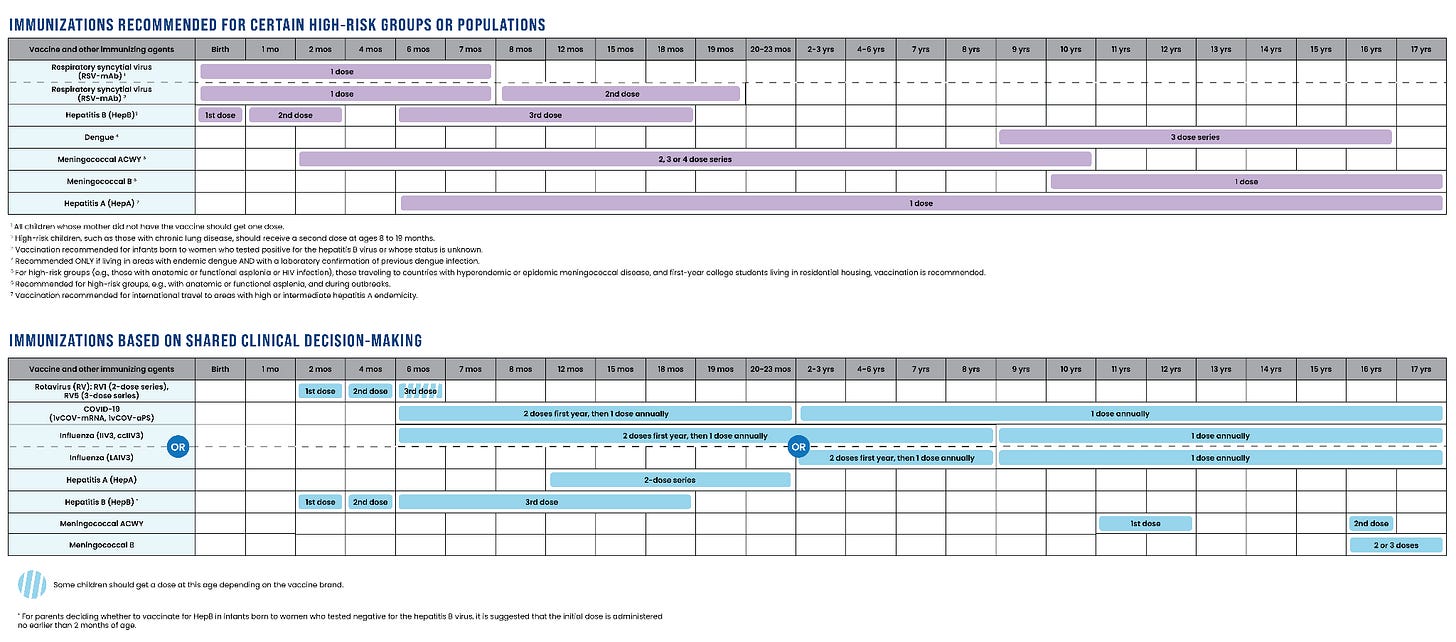

HHS is now recommending some vaccines only for high-risk infants, children, and teens, who have specific health conditions or risk factors. These include RSV, hepatitis A and B, meningococcus, and dengue.

HHS is also recommending the following vaccines based on “shared clinical decision-making”: rotavirus, COVID, influenza, hepatitis A and B, and meningococcus. Families may need to ask for their kids to be vaccinated against these infections.

What’s “shared clinical decision-making”? It means that the choice to vaccinate depends on an individualized conversation between a clinician and patient, based on evidence, personal risk, and preferences — not a universal, one-size-fits-all recommendation.

Immunizations HHS recommends for certain high-risk groups/populations or based on “shared clinical decision-making”:

RSV is the number one cause of hospitalizations among infants and causes an estimated 58,000 to 80,000 hospitalizations among children under 5 every year. HHS continues to recommend a single RSV monoclonal antibody shot for all infants under 8 months who are entering their first RSV season and whose mothers did not receive the RSV vaccine during pregnancy. In other words, there is a universal recommendation for RSV protection: either vaccination of pregnant women or a monoclonal antibody shot for their baby. HHS also continues to recommend a second RSV monoclonal antibody shot for infants 8-19 months at high-risk for severe infection, including those with underlying lung disease or immunocompromise.

HHS recommends hepatitis A vaccination to children traveling internationally to regions where the virus is common or infants based on shared clinical decision-making. In the past, the CDC recommended that all infants be vaccinated.

Under the new HHS guidance, hepatitis B vaccination is recommended only for newborns whose mothers test positive for the virus or whose infection status is unknown. Previously, the CDC recommended that every infant be vaccinated beginning at birth. More on that here. Families may request that their children be vaccinated based on the prior CDC schedule through “shared clinical decision-making.”

Meningococcus, or Neiserria meningitidis, is a bacterial infection that may cause meningitis or sepsis. The CDC previously recommended that all children and teens be vaccinated against meningococcus ACWY as well as infants with immunocompromising conditions and infants and children traveling to countries where meningococcus is common. Meningococcus B vaccine was recommended based on risk. HHS now only recommends meningococcus ACWY vaccine for infants with immunocompromising conditions, infants and children traveling to countries where meningococcus is common, and first year college students living in dorms. Families may request that their children be vaccinated based on the prior CDC schedule through “shared clinical decision-making.”

Dengue vaccine was previously only recommended for children and teens living or traveling to an area where dengue is common (e.g. Puerto Rico) and who’ve previously had dengue. This recommendation has not changed, and later this year, dengue vaccine production will cease due to low demand.

Who makes the rules now?

In the past, childhood vaccine guidelines were based on recommendations made by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), a panel of independent doctors and scientists who reviewed and voted on the evidence.

In June 2025, Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. dismissed all 17 ACIP members and appointed new ones, including individuals known for questioning mainstream vaccine science. He said the shake-up would “restore public trust,” but medical groups warned it undermines the evidence-based process that has guided policy for decades.

In December 2025, President Trump issued a presidential memorandum directing Secretary Kennedy “to review best practices from peer, developed countries for core childhood vaccination recommendations… update the United States core childhood vaccine schedule to align with such scientific evidence and best practices from peer, developed countries while preserving access to vaccines currently available to Americans.”

In response to President Trump’s directive, senior HHS officials including Dr. Tracy Beth Høeg, Acting Director for the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, and Martin Kulldorff, Chief Science and Data Officer for the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, assessed the childhood vaccine guidelines in 20 high-income countries, mostly smaller countries in Western Europe.

The new HHS childhood vaccine guidance was then developed internally at HHS, without independent review, and the ACIP was not consulted, but they were reviewed and accepted by NIH Director Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, FDA Commissioner Dr. Marty Makary, CMS administrator Dr. Mehmet Oz, and Acting CDC Director Jim O’Neill.

Why the government says it changed the rules

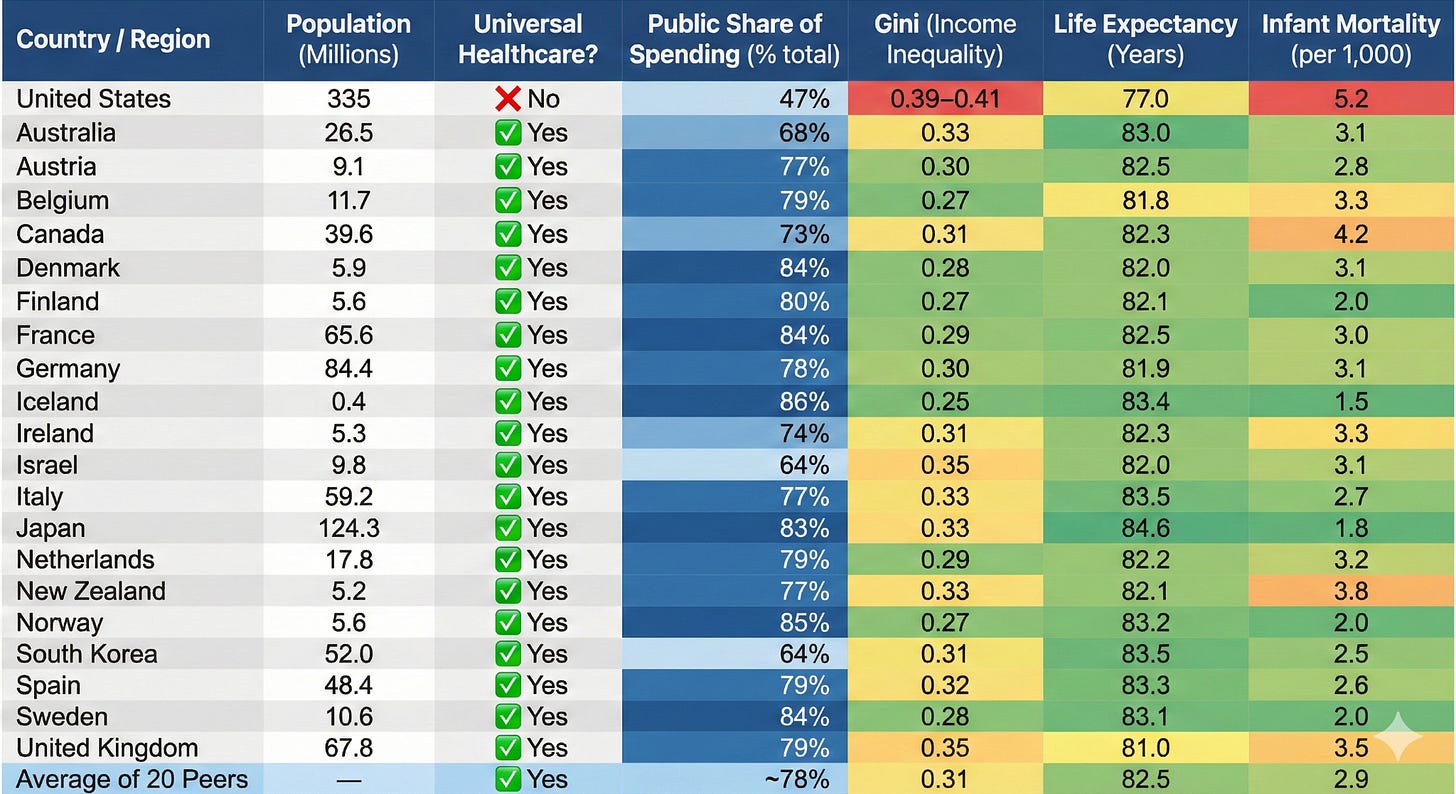

HHS officials said they wanted U.S. recommendations to mirror those of 20 other high-income countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

But it’s comparing apples to oranges. Those countries have universal healthcare, national vaccine registries, and paid parental leave, making vaccine access far easier and more equitable than in the United States. In Denmark, for example, every child is linked to a national medical ID number that triggers automatic reminders, and all care, including hospitalizations for vaccine-preventable diseases, is free (Table 1).

By contrast, millions of U.S. families struggle to find appointments, pay for visits, or travel long distances to clinics. Copying smaller, more equal nations with robust social safety nets may not work in a country as large, diverse, and unequal as the United States.

Table 1. Healthcare and socioeconomic Indicators for the U.S. and 20 other high-income countries

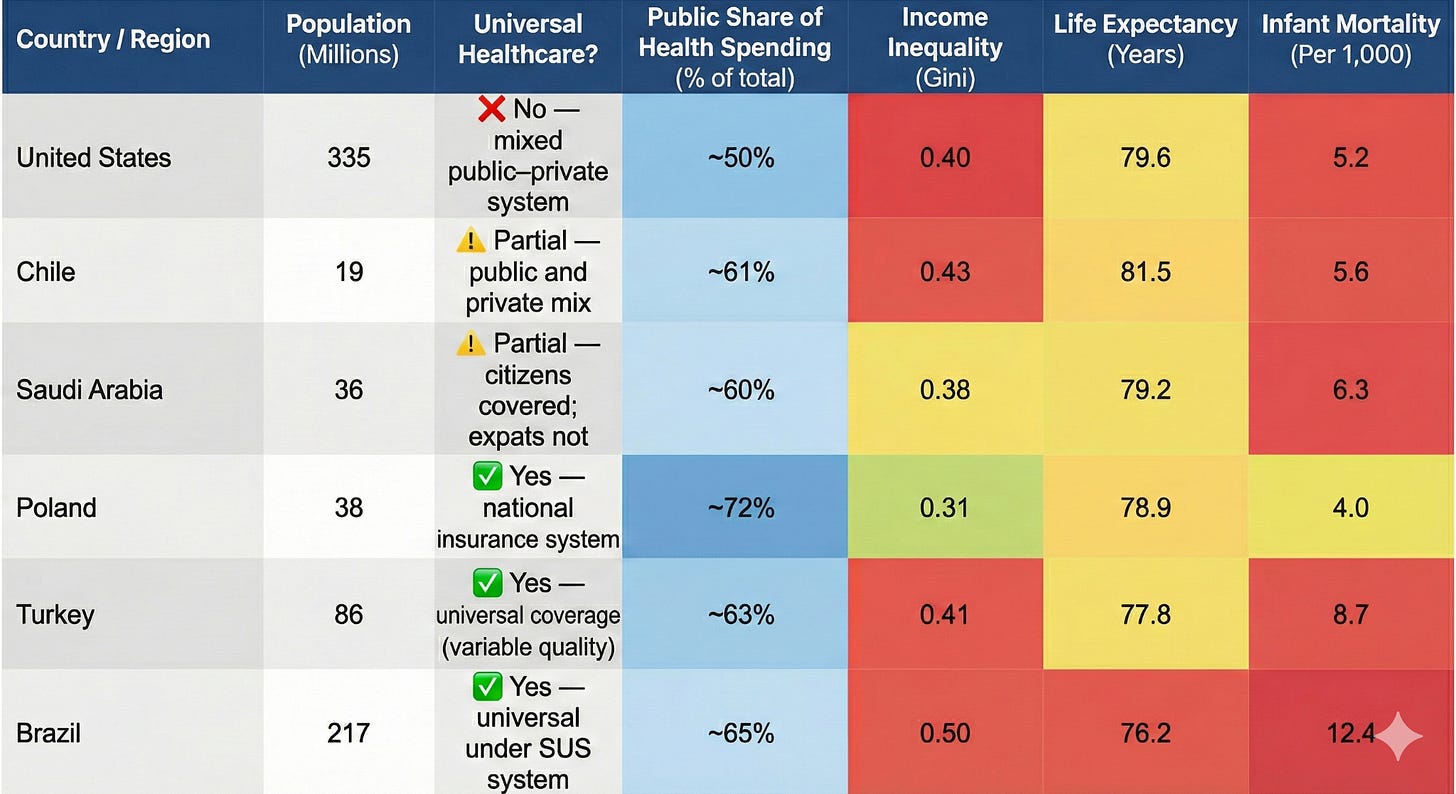

A more accurate apples-to-apples comparison would be with larger, more unequal countries that also lack universal healthcare. Like the U.S., Brazil, Chile, Poland, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia (Table 2) have mixed public and private healthcare systems, wide income gaps, and uneven access to medical care. And all five of these countries continue to include hepatitis A and B, influenza, rotavirus, and meningococcal disease in their routine childhood schedules, alongside other vaccines like MMR, polio, DTaP, Hib, pneumococcal, and HPV.

Table 2. Healthcare and socioeconomic Indicators for the U.S. and 5 countries with similar levels of income inequality, life expectancy, and infant mortality rates

What are other experts saying?

Former CDC Director Dr. Mandy Cohen called the change “confusing” and “a step backwards.”

Dr. Andrew Racine, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said it was “dangerous and unnecessary,” adding, “the United States is not Denmark.”

Dr. Ronald Nahass, president of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, issued a similar warning, calling the overhaul “a reckless step that puts families and communities at risk.”

As vaccination recommendations continue to be politicized, families may want to turn to professional medical societies such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (of which I am a fellow), and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology for advice.

Public trust in vaccines has dropped.

Senior HHS officials said the goal is to “restore trust” by aligning U.S. vaccine policies with “peer, developed nations” and shifting toward “shared clinical decision-making.” They specifically objected to how vaccination recommendations were previously communicated and enforced and linked declining confidence to perceived coercion during the COVID pandemic, poor transparency about risks and benefits, and growing distrust in federal health agencies amid the politicization of public health guidance.

According to KFF and Pew Research Center polling, confidence in childhood vaccines has declined since the pandemic, and fewer than half of Americans now say they trust the CDC as a reliable source. Most adults still view childhood vaccines as effective, but only about half are “highly confident” they’ve been tested enough for safety or that the schedule is safe, especially among Republicans and younger adults.

Political polarization, institutional mistrust, and online misinformation have distorted public understanding of vaccine risks and benefits. While working as an Ebola aid worker in Guinea over a decade ago, I saw people refuse to wash their hands, a basic measure to prevent disease transmission. Their refusal was an act of resistance against the ruling political party. Skepticism about COVID vaccines, and by extension, now all vaccines, can be viewed through that same lens.

Behavioral research also points to psychological drivers: fear of side effects, low perceived risk of disease, and “reactance,” or pushback against perceived coercion. In communities with histories of marginalization or poor healthcare access, skepticism often reflects lived experience rather than ideology.

Offering more choices may also deepen uncertainty. Behavioral studies show that too many options can paralyze decision-making. In one experiment, shoppers offered two dozen jam flavors were less likely to buy than those offered six.

What this means for schools

Each state must now decide which vaccines to require for school. Public health officials expect a patchwork of policies, similar to the fragmented system that existed before the CDC issued its first national schedule in 1977.

Meanwhile, in some states, legislative approval is needed to change requirements — delaying or blocking updates.

In states that scale back, children could enter classrooms without protection against hepatitis A, influenza, or meningococcal disease, potentially reintroducing outbreaks that have been rare for decades. Hepatitis A outbreaks re-emerged in multiple U.S. states between 2016 and 2020 when vaccination rates dropped.

Students moving between states or enrolling in out-of-state colleges could also face mismatched requirements and new paperwork burdens.

How it could affect free vaccine programs

The Vaccines for Children program provides federally funded vaccines to roughly half of U.S. children. With a shorter universal list, officials warn that funding could shrink, limiting doses available through clinics and community programs. That would hit uninsured and underinsured families hardest.

A few states, like Washington and New Mexico, run “universal purchase” programs that buy vaccines for all children, regardless of insurance status. Most states do not. Without new funding, safety net and rural clinics could face shortages.

The new framework could also increase administrative hurdles: pediatricians may need to juggle multiple funding streams depending on which vaccines remain federally covered. Each added layer of paperwork creates friction that slows distribution and limits access.

Questions about new vaccine studies

HHS also announced plans for randomized, placebo-controlled trials to test whether giving fewer or delayed vaccine doses affects children’s health — a move that has raised ethical concerns. Global frameworks like the Declaration of Helsinki state that proven interventions should not be withheld when effective alternatives exist unless compelling scientific justifications outweigh the risks.

The CDC recently awarded about $1.6 million for a trial in Guinea-Bissau comparing hepatitis B vaccination at birth with the country’s current six-week schedule. The study will enroll about 14,000 newborns and follow disease, death, and developmental outcomes.

Guinea-Bissau, one of the world’s poorest nations, has high hepatitis B infection rates, with nearly 20% of adults infected. The WHO recommends a universal birth dose to prevent perinatal and early childhood infection that can lead to chronic infection. Children infected at birth are at high risk of developing cirrhosis or liver cancer later in life and would almost certainly lack access to chemotherapy or liver transplants.

Proponents say the trial exploits a brief “research window”: Guinea-Bissau’s health ministry plans to introduce a universal birth-dose policy in 2027, but until then, vaccination starts at six weeks, allowing comparison between the future policy and the current standard.