The Migration of Trust

As measles returns and senators debate vaccines, a deeper problem is coming into focus: science has never been stronger, yet trust in the institutions that produce it has never been more fragile.

by Drs. Céline Gounder, Marcello Ienca, Zeke Emanuel

This week’s Senate hearing on measles and vaccine safety took an unexpected turn. Instead of focusing only on viruses and vaccines, it turned into a conversation about trust and why so many Americans no longer have much of it.

Senator Bernie Sanders asked NIH Director Jay Bhattacharya why, despite overwhelming scientific evidence, confidence in the health care system and public health institutions has fallen so far. Sanders pointed to familiar frustrations: unaffordable care, high drug prices, and a widespread belief that powerful corporate interests frequently carry more weight than patients.

Bhattacharya agreed that trust has eroded, but traced much of that erosion to the pandemic years. He pointed to shifting guidance, opaque decisions, and moments when uncertainty wasn’t communicated clearly. From that perspective, mistrust grew as people felt misled, talked down to, or excluded from decisions that shaped their lives.

Both explanations ring true. But neither fully explains what’s happening now nor why mistrust so often shows up not as healthy skepticism, but as confidence in conspiracy theories, fringe claims, and people with no relevant expertise at all.

What was largely missing from the exchange was a deeper shift that has been unfolding for some time: Trust hasn’t just declined. It’s moved.

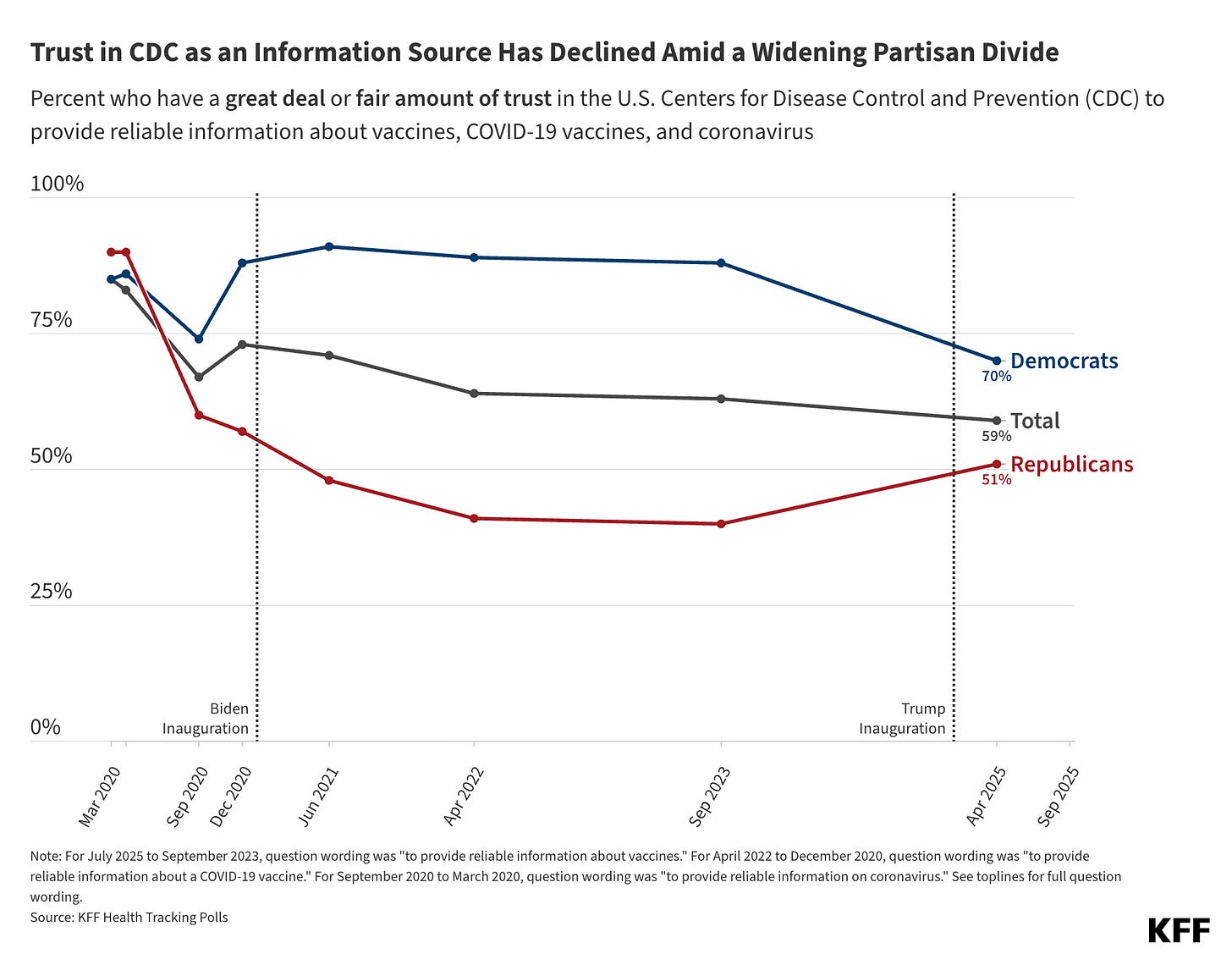

In today’s information landscape, credibility flows less through institutions and more through networks — friends, influencers, podcasters, group chats, and algorithmically boosted voices that feel familiar, relatable, and emotionally aligned. That helps explain how people can say they “believe in science” while simultaneously rejecting the institutions that produce and communicate it. It also helps explain a striking gap in the latest KFF polling: while fewer than half of Americans (47%) say they trust the CDC to provide reliable vaccine information, 86% say they trust their own doctor or health care provider for reliable health information, and 81% say they are confident the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine is safe for children.

That dynamic was on display again this fall, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention quietly revised its webpage on vaccines and autism. At the direction of Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the CDC replaced its long-standing statement that “vaccines do not cause autism” with language suggesting the evidence is “not conclusive.” The scientific response was immediate and unequivocal.

The change didn’t come from CDC scientists, and it wasn’t driven by new data. Inside the agency, staff described it as destabilizing. Outside it, vaccine opponents treated it as vindication. In an attention economy built for spectacle, the edit didn’t read as nuance. It read as confirmation.

Within hours, conspiracy networks framed the change as proof that decades of research had been misleading. That narrative persists despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. The original autism claim rested on a study of 12 hand-picked patients, no controls, and a lead author with serious financial conflicts. Large epidemiologic studies across multiple countries, decades of surveillance, and countless independent analyses have found no causal link between vaccines and autism. The evidence here is stronger than for nearly any other safety question in modern medicine.

Taken together, the Senate hearing and the CDC website edit illustrate how public health authority now operates. Scientific consensus remains strong. Institutional credibility, far less so. Polls still show that many Americans trust science in the abstract, but confidence in the institutions that represent it has thinned.

The reasons go beyond politics. They reflect a broader shift in how people encounter information and authority. For much of the 20th century, expertise flowed vertically: experts spoke, journalists translated, and the public largely accepted their authority. Today, information moves sideways. Trust accumulates through social networks rather than institutions.

On those platforms, credentials matter less than connection. A confident influencer speaking from a kitchen table can feel more trustworthy than a scientist reading from prepared remarks. Psychologists call this the “warmth-competence” gap: people judge trust not only by expertise, but by empathy. Institutions often signal competence but little warmth. Influencers flip that balance, and algorithms reward them for it.

This helps explain why misinformation spreads even among people who consider themselves scientifically minded. Many Americans feel confident judging health information on their own, yet remain skeptical of institutions that once mediated it. In that space, simple, confident explanations travel faster than careful ones.

Social media sharpens the imbalance that Bhattacharya described. Scientists are trained to speak in probabilities and evolving evidence, yet online platforms reward clarity, confidence, and emotional force. When uncertainty is left unspoken, trust erodes. When it is spoken plainly, it often performs poorly. Nuance moves slowly. Certainty goes viral. Expertise can sound hesitant, while misinformation sounds sure of itself.

As science has become more rigorous, coordinated, and technically sophisticated, it has also grown more distant from everyday experience. Evidence has strengthened, but the distance between institutions and the public has widened, especially in an information environment that rewards immediacy, authenticity, and emotional connection.

Episodes like the CDC’s vaccine-autism edit are revealing not because they alter the science, but because they show how fragile institutional authority has become. A single politically driven edit, amplified online, overshadowed decades of evidence in a matter of hours. It didn’t create mistrust so much as activate a system already primed to redirect it.

Trust hasn’t vanished. It has been redistributed across a very different information landscape. It now gravitates toward voices that feel immediate and relatable, rather than institutions built for accountability and rigor. In that environment, accurate science can struggle to stay legible, even when the stakes are as clear as a measles outbreak.

Research suggests that trust holds better when institutions make their independence visible, explain how decisions are made, and engage communities earlier rather than reactively. It also holds better when scientific communication pairs rigor with humility, acknowledging uncertainty without retreating into jargon or defensiveness. Warmth and transparency, in this sense, operate less as stylistic choices than as signals of credibility.

Measles is a reminder of what’s at stake. Public health depends not only on evidence, but on shared confidence in the institutions that generate and communicate it. When trust moves faster than those institutions can adapt, preventable disease finds room to return.

The science did not fail us. But the institutions that carry it can no longer rely on evidence alone to be believed.