What the CDC’s Vaccine Language Shift Reveals About Pseudoscience

Researchers see a pattern in how unverified studies gain traction online, shaping perceptions of official science before data can catch up

When the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention rewrote its vaccine safety webpage last month, it landed like a bombshell.

The agency’s long-standing statement, “Vaccines do not cause autism” was replaced with the far more misleading “Some studies have found possible links between vaccines and autism spectrum disorder.”

The revision appeared just weeks after the McCullough Foundation, a group led by Dr. Peter McCullough and discredited British ex-physician Andrew Wakefield, whose fraudulent 1998 paper ignited decades of vaccine misinformation, released an 82-page self-published paper claiming “a significant vaccine-autism link.” The -report raised immediate concerns about independence, transparency, and conflicts of interest.

McCullough is the chief scientific officer of The Wellness Company, which sells ivermectin and a supplement claimed to counteract the toxic effects of COVID spike protein. His board-certifications in internal medicine and cardiology were both revoked by the American Board of Internal Medicine after it concluded that he repeatedly made public statements about COVID, its treatments, and vaccines that were false, misleading, or unsupported by scientific evidence. Both McCulllough and Wakefield have had multiple papers retracted. Wakefield, notably, received more than £400,000, or more than $500,000 based on current conversation rates, from lawyers preparing lawsuits against vaccine manufacturers. Those payments were undisclosed and contributed to the retraction of his 1998 Lancet paper.

The report also lists funding from both the McCullough Foundation and the Bia-Echo Foundation, run by Nicole Shanahan, Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s 2024 running mate, who has promoted pseudoscientific autism theories. Yet the authors still claim “nothing to declare” under conflicts of interest.

On X (formerly Twitter), McCullough celebrated the CDC’s update as proof that his foundation’s work had influenced federal policy. “CDC Backed by McCullough Foundation Report Changes Vaccine-Autism Stance,” he wrote, adding that the agency had “followed point-by-point, evidence-based inferences.” In another post, McCullough asserted that the CDC’s edit “responds directly to McCullough Foundation analysis.” And in a written response, McCullough said, “CDC responded to the McCullough Foundation Report by making changes on their website. This appeared to be in direct response to our publication on October 27, 2025.”

The Department of Health and Human Services, which includes the CDC, did not respond to a request for comment.

Inside the CDC, the reaction to the website change was alarm, not celebration. “It wasn’t vetted the way it should have been,” said one scientist who has worked on autism, speaking on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak to the media. “People were stunned. The change made it look like we’d shifted our position, when in fact the science hasn’t changed at all,” the scientist said, adding that the decision did not originate from the agency’s vaccine or autism experts. “They weren’t in the loop.”

How a Not-Peer-Reviewed Paper Became ‘Proof’

The McCullough report contained no new or original data about the alleged autism-vaccine link and cited numerous papers from predatory publishers, which prioritize financial or reputational gain, often at the expense of scientific rigor, transparency, and integrity. It also didn’t include an explanation of the methodology used to select studies and analyze data. Yet its presentation — long, number-heavy, and full of scientific jargon — gave it the look of authority.

Dr. Daniele Fallin, dean of Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health, said the authors inverted the scientific method. “That’s not how science works. You don’t start with the answer and then go hunting for the evidence that fits. You start with a question, a hypothesis, and you test it. Then you report what you find, whether or not it matches what you expected.”

Rebecca Schmidt, an autism expert at UC Davis, said the report “treats small, uncontrolled studies, including toxicology and mechanistic papers, as if they have the same evidentiary weight as large epidemiologic studies.” “Research conducted in animals much of the time does not translate to humans,” she said, “because our brain development and structures and resultant behavioral outcomes are very different.” She added that cellular models “cannot always capture the full complexities of in vivo responses that occur within the context of developing humans.”

Critics said the authors appeared more focused on counting studies that showed a “possible link than on the quality of the studies. This approach treats tiny, unreliable, unscientific studies the same as the large, well-designed ones necessary to test cause and effect.

Craig Newschaffer, dean of the Penn State College of Health and Human Development and an autism epidemiologist, said that “this continual shifting of vaccine exposure variant of particular concern (e.g., MMR, thimerosal, aluminum, cumulative doses, etc.) has been speculated to be a tactic that allows general vaccine suspicion to remain elevated, since it is challenging and time-consuming to mount legitimate scientific investigations that accumulate sufficient evidence related to ever-evolving hypotheses.”

Mechanics of Manufactured Legitimacy

The controversy over the CDC’s revision isn’t just about evidence. It’s about how pseudoscience is made to look like science. The McCullough Foundation report is a textbook example, using formatting, jargon, and long reference lists to mimic rigor.

Stephan Lewandowsky, a cognitive psychologist at the University of Bristol who studies misinformation, said the report reflects a broader shift in how false claims spread. “They are creating facsimile science, pseudoscience that is meant to look as much like science as is possible,” he said. “At first glance, it looks like science — it has graphs, it has references — but it’s just their game. To not be swayed by that requires a lot of skill.”

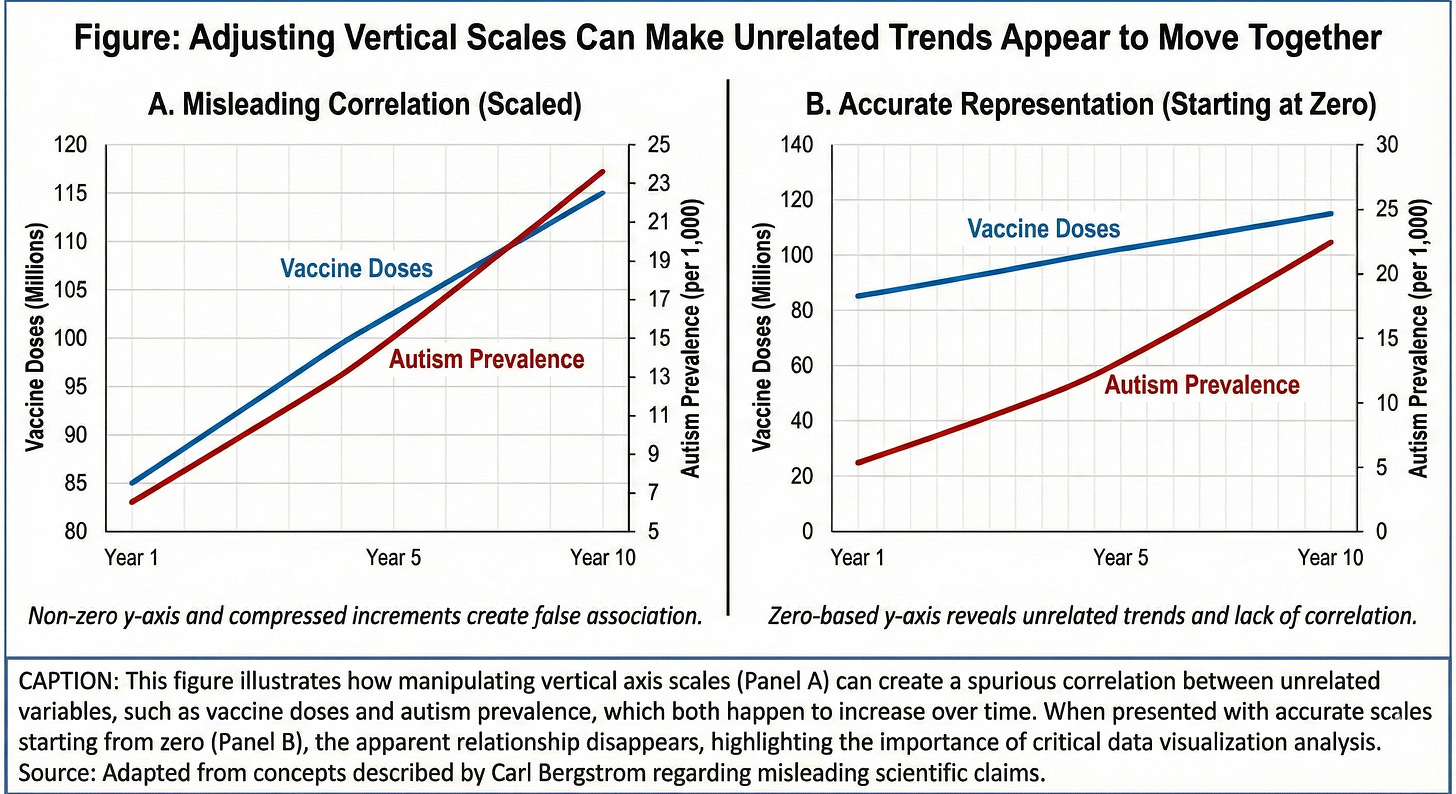

Carl Bergstrom, a biologist at the University of Washington who studies how scientific claims gain credibility, said the report “illustrates nearly every way misleading information can be made to look credible.” One of its central figures plots vaccine doses and autism rates on two different vertical scales, one of which doesn’t start at zero. The result is a pair of unrelated trends that seem to rise together. “We’ve seen this sort of thing before in antivax propaganda,” he said.

The illusion comes entirely from scaling: vaccine coverage is shown in tiny increments, while autism prevalence is squeezed into a much smaller range. On the page, the lines appear to track together even though the connection is manufactured. Bergstrom noted that average college tuition and autism diagnoses can be made to look correlated for the same reason, both happen to increase over time.

Figure: Adjusting the vertical scales can make unrelated trends appear to move together.

Newschaffer explained that population-level correlations, “when data on exposure and outcome available only at the group-level are used to infer a causal relationship at the individual level, are considered inherently weak.”

This is how pseudoscience cloaks itself, Bergstrom said. Numbers project authority, graphics suggest precision, and most readers won’t examine the method. “It’s quantitative theater,” he said. “The graph looks convincing” long before anyone questions the data.

The report’s long list of citations serves the same purpose. “The stack of citations becomes a prop,” Bergstrom said. “If there are hundreds, readers stop asking whether any of them are credible.” Many of the sources are ideological or non-peer reviewed, and the report even cites Wakefield’s retracted Lancet paper as if it were legitimate.

Scientific-sounding language fills in the gaps: terms like “neuroimmune injury” and “mitochondrial dysfunction” that add gravitas without explanation. “It’s the appearance of science without the substance,” Bergstrom said. “You get all the aesthetics of research, none of the rigor.” By labeling findings as “possible,” he added, the authors imply causation without claiming it outright. “It’s a linguistic sleight of hand… using the scientific virtue of caution as a marketing tool for doubt.”

Dr. David Mandell, a child psychiatrist and autism researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, said his review of the report was troubling. “On every page, I found at least one factual error, many of which seemed intentional,” he said. “That tells you either the authors don’t understand the material, or they’re deliberately trying to mislead the reader.”

Noise Wins When Science Stays Silent

That tactic, using uncertainty and scientific language to spread misinformation, thrives when institutions stay silent.

“When trusted sources hesitate to clarify,” Bergstrom said, “these narratives fill the vacuum. The longer the silence, the truer the misinformation feels.”

“When we don’t explain changes, people fill the silence with misinformation,” said Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, who until recently led the CDC’s immunization program. “Public health can’t go quiet, especially on something as sensitive as vaccines and autism.”

Mandell said the sheer volume of misinformation makes it impossible for scientists to counter every claim. “It’s whack-a-mole,” he said. Misinformation spreads quickly because it speaks to emotion, while science advances slowly because it requires evidence, he said. “Misinformation is emotionally intuitive,” he added. “Science takes time. Those speeds don’t match.”

What Autism Science Actually Shows

Experts say the rise in autism diagnoses is mostly due to changes in how autism is defined and recognized, not because it has become more common. The definition has broadened, doctors screen more often, and schools now require formal evaluations before kids can get certain services.

The increase, then, is seen in kids “who are less profoundly impacted… who are verbal, who have IQs in the normal to above normal range,” Mandell said. Meanwhile, the number of children with more severe autism has stayed the same. More awareness also means that teenagers and even adults are being diagnosed for the first time. Mandell noted that “the largest increase in new diagnosis of autism is coming in adolescents and young adults.”

For scientists who study autism, the McCullough Foundation report’s claims not only ignore decades of research. They distort the complex picture of what autism actually is.

Brain imaging studies show differences months before most vaccines are administered. “We have found brain differences as early as 6 months of age in those who go on to develop autism,” said Dr. Joseph Piven, a psychiatrist and autism researcher at the University of North Carolina. “This is a group difference (autism vs. non-autism) and is important but, more importantly, we have found brain differences at 6 and 12 months of age that accurately predict who will develop autism. … a vaccine given later or exactly coincident with our MRI could not be responsible for the brain changes we see—that take time to develop.”

That picture, scientists say, is supported by hundreds of studies and two decades of replication. A 2014 meta-analysis involving 1.2 million children found no association between vaccines and autism. And a 2019 Danish study following 657,000 children confirmed the same result, even among siblings of autistic children.

“There is no credible way to frame autism as being the result of one cause. The best evidence for this is genetic. About 80% of cases are due to the interaction of multiple genes of small effect,” Piven said. “The overwhelming evidence is that there are multiple pathways to autism.”

Fallin points to “fetal origins of the biology of ASD [autism spectrum disorder], well before a child receives the MMR vaccination.” Rather than exposures after a child is born, Schmidt, who investigates autism’s environmental risk factors, said the data point to conditions surrounding pregnancy. “We see consistent associations with maternal health, things like obesity, diabetes, infections during pregnancy, nutritional deficiencies, and exposure to pollutants,” she said.

[Correction: This article was updated at 4:05 p.m. ET on December 22, 2025, to correct Dr. Joseph Piven’s quotes.]