Wildfire Smoke Is More Dangerous Than We Thought

New research shows long-term smoke exposure raises the risk of death, even at low levels

The Hidden Health Risk in the Air

Wildfire season has become a familiar part of life in much of the United States. Skies turn hazy, the air smells of burning trees, and daily routines change as people try to limit time outdoors. What has been less visible is what happens when that smoke returns year after year, lingering long after the flames are out.

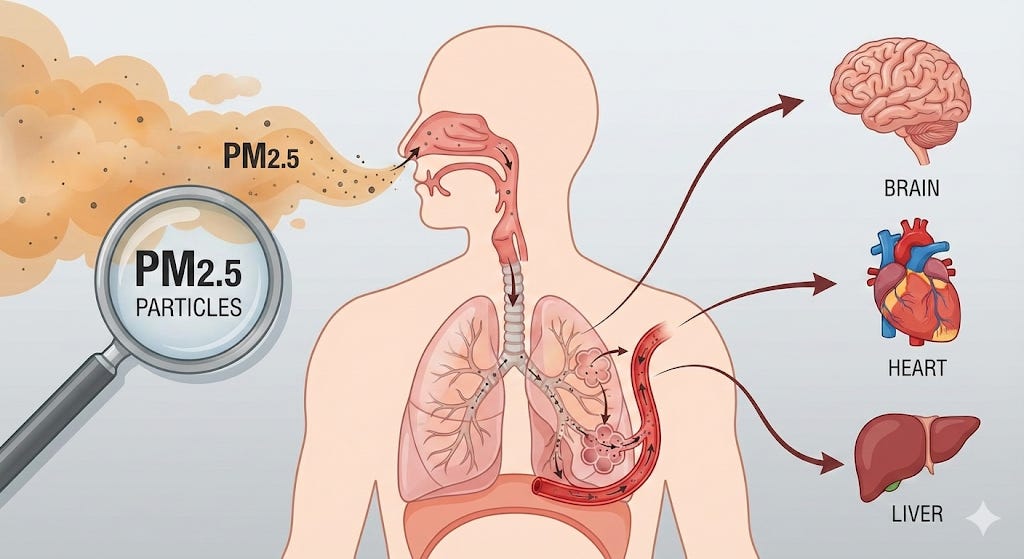

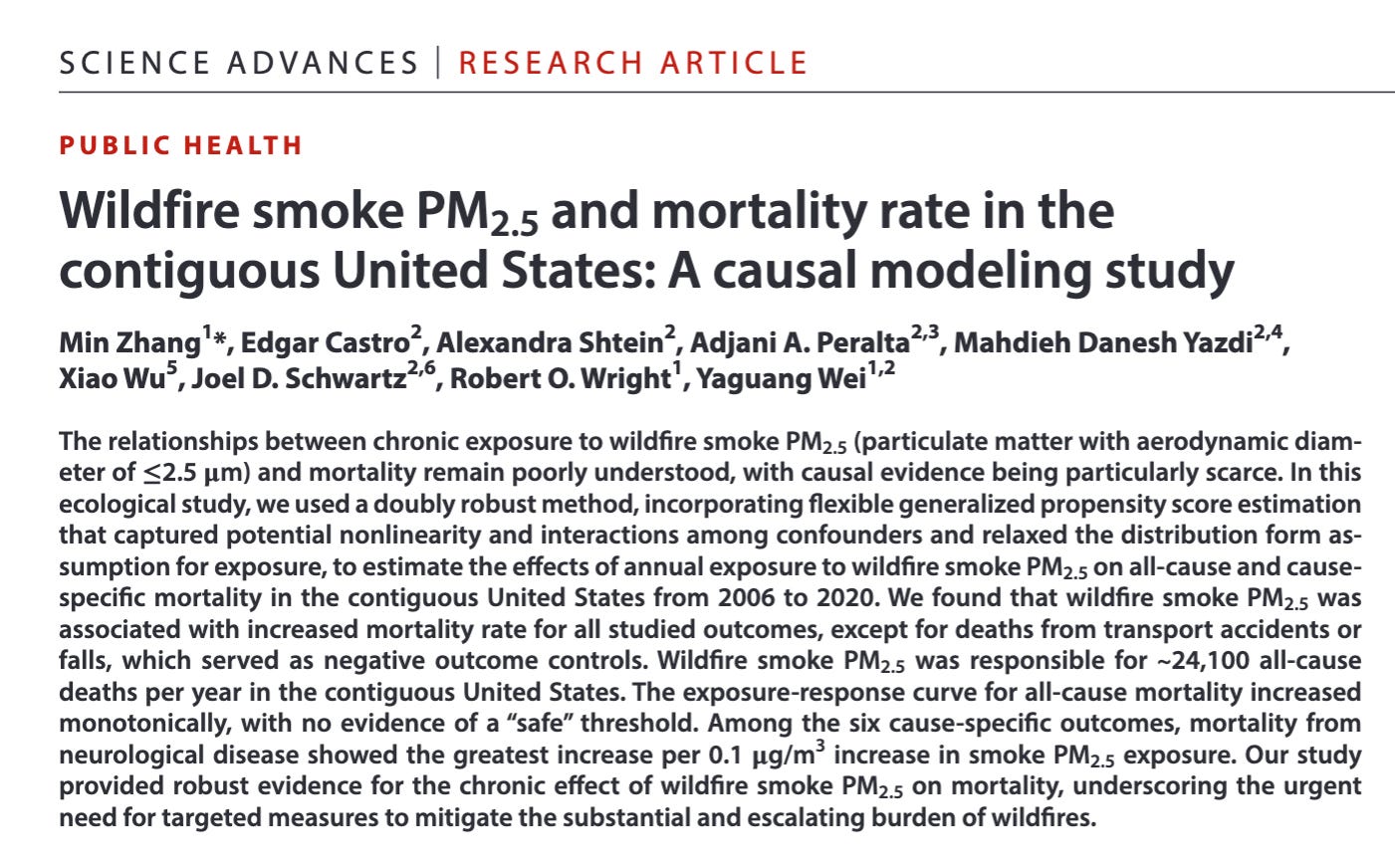

A new study adds weight to a growing concern among public health researchers: long-term exposure to wildfire smoke is linked to higher death rates across the country. The research estimates that fine particles from wildfire smoke, known as PM2.5, contribute to roughly 24,000 premature deaths each year in the United States, even though average exposure levels are relatively low. PM2.5 refers to tiny air pollution particles smaller than 2.5 micrometers, about 30 times thinner than a human hair, that can be breathed deep into the lungs and enter the bloodstream, where they can affect many organs in the body.

Smoke exposure that builds quietly

The study, published in Science Advances, analyzed mortality and air pollution data from 2006 to 2020 across more than 3,000 U.S. counties. Instead of focusing on short-term smoke events, the researchers looked at average yearly exposure to PM2.5 that came specifically from wildfires.

On average, wildfire smoke added about 0.4 micrograms of PM2.5 per cubic meter of air each year. That amount is far lower than what people experience during severe smoke days, but the effects added up. The analysis found that for every small increase in annual wildfire smoke exposure, overall death rates increased. When applied nationwide, those small increases translated into tens of thousands of deaths each year.

No clear line between safe and unsafe

One of the most striking findings was what the researchers did not find: a clear threshold where wildfire smoke stopped being harmful. Mortality risk rose steadily as long-term smoke exposure increased, with no sign of a safe lower limit.

This result echoes earlier epidemiological research on PM2.5 from other sources, but it carries special weight for wildfire smoke, which has a different chemical makeup. Smoke particles from wildfires are rich in compounds produced by burning vegetation and buildings, and scientists believe these particles may trigger inflammation throughout the body, not just in the lungs.

Health effects beyond the lungs

Lung disease is strongly linked to wildfire smoke exposure. Numerous studies on the health effects of wildfire smoke have found increases in asthma attacks, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease flare-ups, and respiratory hospitalizations during and after smoke events.

But the new study found elevated mortality risks across a wider range of diseases. Deaths related to neurological conditions showed some of the strongest associations, followed by cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Other epidemiological studies have reported mixed but increasingly suggestive evidence linking wildfire smoke to heart attacks, strokes, and heart failure, particularly among people with pre-existing conditions.

The researchers caution that measuring individual exposure remains difficult. Smoke often coincides with extreme heat, stress from evacuations, and other pollutants like ozone. Many studies rely on county-level exposure estimates, which can miss important differences in how much smoke individuals actually breathe.

Uneven exposure, uneven risk

The study also found that the health impacts of wildfire smoke were not evenly distributed. Stronger associations appeared in rural counties, where smoke exposure is often higher and access to health care may be more limited. Effects were also more pronounced in areas with larger populations under age 65, suggesting that wildfire smoke does not only affect the very old or frail.

Other research has consistently identified children, older adults, pregnant people, and individuals with heart or lung disease as especially vulnerable. Children, in particular, breathe more air relative to their body size and have developing lungs, raising concerns about long-term effects on lung growth and respiratory health.

Housing quality, workplace, and access to medical care also influence how much smoke people are exposed to and how their bodies respond.

A growing national burden

Health researchers have begun estimating the broader cost of wildfire smoke. Modeling studies suggest that smoke-related PM2.5 exposure already causes billions of dollars in health care costs and lost productivity each year. Under climate scenarios with more frequent and intense wildfires, those costs could rise sharply in future decades.

At the same time, major gaps remain. Long-term effects of repeated childhood exposure are still being studied. The effectiveness of different protective measures varies widely depending on housing, behavior, and resources. And separating the health effects of smoke from those of heat and other environmental stressors remains a challenge.

For decades, wildfire smoke was treated as a short-lived side effect of a natural disaster. The accumulating evidence tells a different story. As smoke becomes a regular part of the background air in large parts of the country, its health effects no longer appear limited to emergency rooms during bad fire weeks, but are embedded in the slower math of population health, where small exposures, repeated often enough, leave a measurable mark.