Fact Check: Does the Rotavirus Vaccine Cause Dangerous Bowel Blockages?

Why RFK Jr.’s claim about “deadly diseases” and the rotavirus vaccine is misleading.

“The rotavirus killed approximately 3 children per year. And I think since the rotavirus vaccine has come online or has been recommended, that has dropped to around 2 children per year… If you’re giving 3 million vaccines to prevent 1 death, then you have to make sure that the vaccines are not causing any damage. Various rotavirus vaccines have been linked to very, very serious and deadly diseases, including intussusception.” (jump to 6:49)

— HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

No, the rotavirus vaccines don’t cause “deadly” side effects.

Rotavirus infections are more likely to cause intussusception.

No, the rotavirus vaccines don’t cause “deadly” side effects.

When Robert F. Kennedy Jr. warns about vaccines, his arguments often rely on half-remembered history. In this case, he points to a long-discontinued rotavirus vaccine from the 1990s that was briefly linked to a rare intestinal problem called intussusception and then claims the same danger exists today. It doesn’t.

The rotavirus vaccines in use now were developed after that early version was pulled from the market, and they’ve been safely protecting infants for nearly two decades.

Rotavirus once sent between 55,000 and 70,000 American children under five to the hospital every year and killed 20 to 60 infants annually. In low-income nations, it remains a major cause of severe diarrhea and child death.

A first-generation vaccine called RotaShield, approved in 1998, was pulled from the market in 1999 after researchers discovered it caused a rare intestinal condition called intussusception in roughly 1 out of every 10,000 infants.

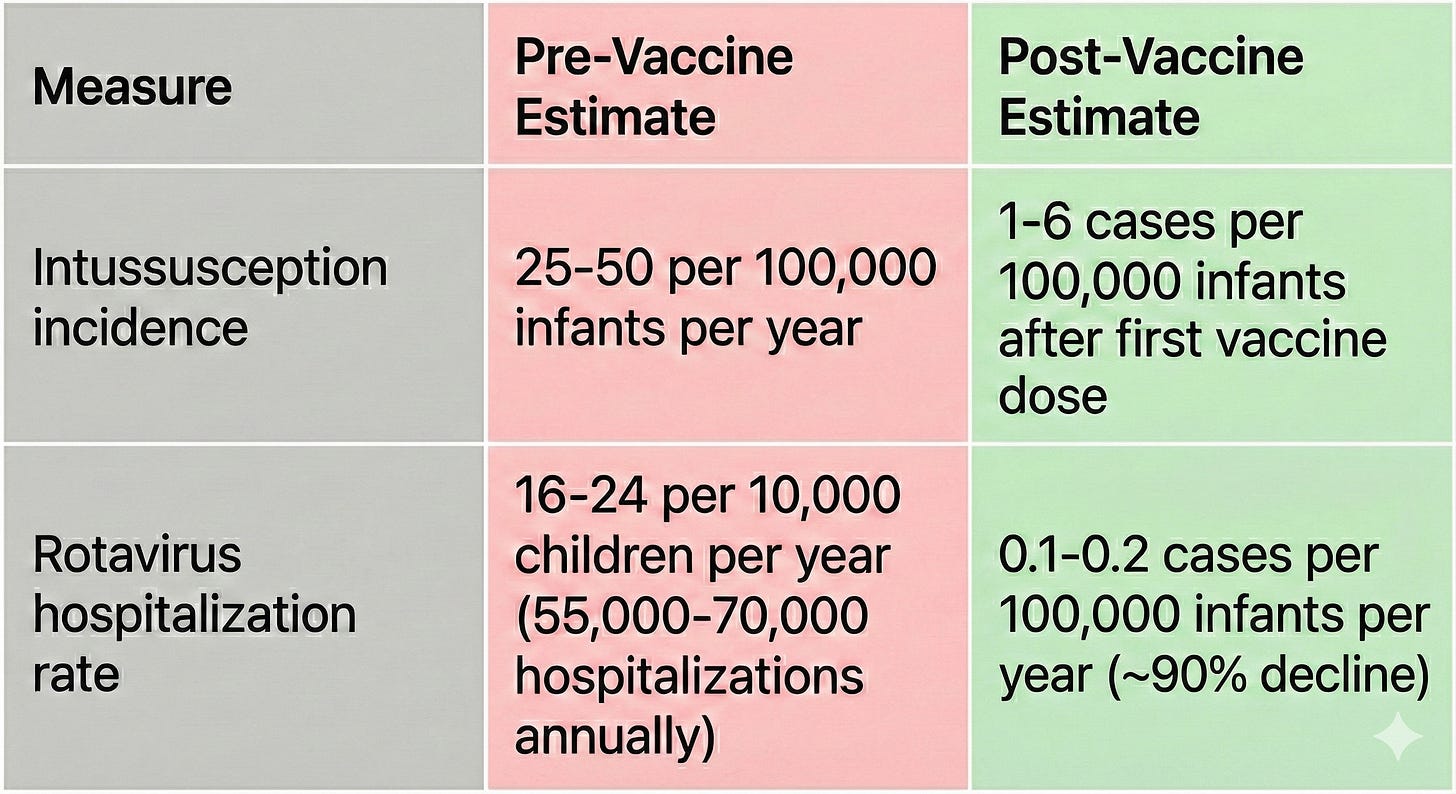

But today’s rotavirus vaccines, RotaTeq and Rotarix, are different. They were redesigned, tested in large studies with tens of thousands of infants, and have been safely used around the world for almost twenty years. There’s still a very small chance of intussusception — about 1 to 6 extra cases for every 100,000 babies who get the vaccine each year — but that’s lower than the rate of intussusception before vaccination, which was about 25 to 40 cases per 100,000 infants.

In other words, the current vaccines pose a far smaller risk than the disease itself.

Table 1. A comparison of intussusception and hospitalization rates before and after the current rotavirus vaccines were introduced

What is intussusception, anyway?

Intussusception happens when part of a baby’s intestine slides into itself, a bit like a collapsing telescope. It can block food and blood flow, causing pain and vomiting. In the United States, intussusception is a medical emergency but is rarely fatal due to access to treatment with an air enema or minor surgery; the fatality rate for intussusception is estimated at less than 0.1%.

Other viral infections, like adenovirus, enterovirus, and norovirus, are also common causes of intussusception, but in most cases, doctors never find a clear cause.

In the late 1990s, doctors noticed more cases of this condition after children received RotaShield. Within ten months, the old rotavirus vaccine was withdrawn, a move that showed vaccine safety monitoring was doing its job.

Rotavirus infections are more likely to cause intussusception.

The irony is that the very virus the vaccine protects against is more likely to cause intussusception than the vaccine itself.

“The vaccine strain does it much less often because it’s weaker,” Offit said.

It’s a bit like the COVID vaccines and myocarditis: both the virus and the vaccine can affect the heart, but infection itself is much more likely to cause problems. In the same way, both rotavirus infection and the rotavirus vaccine can very rarely cause intussusception, but it happens far more often after infection than after vaccination. The vaccine’s risk is tiny compared with the danger of severe dehydration and hospitalization from rotavirus infection.

Since vaccination became routine, overall U.S. intussusception rates have declined, suggesting the vaccine prevents more cases than it causes.

A safer generation of vaccines

Dr. Paul Offit, a pediatrician and vaccine scientist who helped develop RotaTeq, remembers that era vividly.

“RotaShield was a real but rare cause of intussusception,” Offit said. “After the first dose, the relative risk was maybe 25 to 30 times greater than in unvaccinated kids. After the second dose, that risk dropped dramatically.” That first rotavirus vaccine was pulled from the market in 1999.

The next vaccines — RotaTeq (approved in 2006) and Rotarix (approved in 2008) — were built to be safer. Both underwent extensive safety trials before approval.

A 2006 phase III clinical trial of nearly 70,000 infants found no significant difference in intussusception rates between babies who received the RotaTeq vaccine and those who got a placebo.

Rotarix also passed large safety tests. A phase III study of more than 63,000 infants in Latin America and Finland found no extra risk of intussusception within a month of either dose.

After both vaccines were licensed, safety systems continued to monitor them. A 2014 post-licensure study found a very small increase — about 1 or 2 extra cases per 100,000 babies — after the first dose only. No additional risk was observed with later doses.

“If you have 100,000 babies getting vaccinated, one or two might have this reaction,” Offit said. “But before the vaccine, tens of thousands were hospitalized every year.”

Since rotavirus vaccines were introduced in 2006, hospitalizations for rotavirus infections among U.S. children have declined by 80% to 90%.

RFK Jr’s numbers don’t add up.

Kennedy told CBS News, “If you’re giving 3 million vaccines to prevent one death, you have to make sure the vaccines aren’t causing any damage.” But his math is wildly off. The vaccine prevents thousands of hospitalizations and emergency department visits every year in the U.S., and in lower-income countries, it’s estimated to save about 165,000 young lives annually.

“Rotavirus was the biggest single cause of death in infants and young children,” Offit said. “Our vaccine now saves more lives globally than almost any other childhood vaccine.”

Verdict

An early version of the rotavirus vaccine (RotaShield) was associated with an increased risk of intussusception. But today’s vaccines, RotaTeq and Rotarix, are much safer, with only a tiny risk that’s vastly outweighed by the protection they offer.

“To choose not to get that vaccine,” Offit says, “is to choose a very real risk of rotavirus infection, and that’s not a disease you want.”

Rating: ❌ False

In reality, rotavirus used to hospitalize tens of thousands of U.S. children and kill up to 60 each year before vaccination, while the current rotavirus vaccines prevent millions of cases and more than 160,000 child deaths globally every year. Kennedy’s claim misrepresents both the disease’s danger and the vaccine’s proven safety.