How Industry Helped Put Protein at the Center of America’s Diet

The quiet influence behind the new dietary guidelines and what science really says about eating too much protein.

Protein Is Suddenly Everywhere

Protein has become America’s favorite nutrient. It’s added to everything from bottled water to ice cream and promoted as the answer to hunger, tiredness, and even self-control.

Now, the federal government has joined in. Last week, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans put protein front and center, encouraging higher intakes for many adults and telling people to prioritize protein at every meal.

This marks a clear break from decades of advice that urged moderation and a win for industries that have spent years branding their products as “real food.”

It sounds like progress, but the story is more complicated. What looks like a simple update in nutrition science is actually a major policy shift, shaped by industry influence and limited scientific evidence.

What Happened to the Science

In late 2024, a group of independent scientists known as the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) finished a detailed report for the federal government. Their main advice was clear: eat less red and processed meat and more plant-based proteins, like beans, lentils, and nuts.

But when the new Dietary Guidelines for Americans came out, much of that advice was gone. Clear language about eating less red and processed meat was removed or watered down. Instead, the Departments of Health and Human Services (HHS) and Agriculture (USDA) relied on a separate review written by a smaller, government-contracted team.

Public records show that six of the nine scientists on that new review team had financial ties to the meat, dairy, pork, or supplement industries:

Heather Leidy, PhD, received research funding from beef, pork, egg, and food industry groups and serves on the advisory board of a snack company.

Leidy received research funding from the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, the Beef Checkoff Program (a producer- and importer-funded marketing and research program), the National Pork Board, the Egg Nutrition Center, the General Mills Bell Institute of Health and Nutrition, and Novo Nordisk. She’s on the advisory board of Rivalz (plant-based snack brand).

J. Thomas Brenna, PhD, received funding and consulting fees from beef and dairy groups.

Brenna received research funding from the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association/North Dakota Beef Council, Dairy Management, the National Dairy Council, and Danone (the food and beverage corporation). He’s consulted for the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association/Texas Beef Council, Nutricia (subsidiary of Danone), General Mills, and the Washington Grain Commission. He’s received reimbursement for travel from the Global Dairy Platform and the American Dairy Science Association. He’s the founder of Adepa Life (an online health/wellness company selling gut supplements). And he’s on the board of Seafood Nutrition Partnership.

Ameer Taha, PhD, received funding from dairy industry organizations.

Taha received research funding from the California Dairy Innovation Center and Fonterra Limited (dairy industry).

Donald Layman, PhD, co-owns a protein supplement company and has received funding and fees from beef, dairy, and nutrition groups.

Layman is a co-owner of Metabolic Designs, a company that sells protein supplements, and the Director of Research for the Egg Nutrition Center. He’s received research funding and consulting fees from the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, the National Dairy Council, and Agropur (Canadian dairy cooperative). He’s also received honoraria and consulting fees from Functional Medicine. He has served on the advisory board of the Nutrient Institute and Herbalife.

Michael Goran, PhD, advised infant formula companies and received funding from dairy, food, and low-carb diet foundations.

Goran was a scientific advisor to Else Nutrition, Bobbie Labs, Begin Health, and Yumi Foods. He has also received research funding from the Gerber Foundation (the philanthropic arm of the infant food manufacturer), the National Dairy Council, Nestle USA (the food and beverage company), and the Dr. Robert C. Atkins Foundation (associated with the Atkins diet brand and related low-carbohydrate products).

Jeff Volek, PhD, RD has financial ties to diet, wellness, and food companies that market high-protein and low-carbohydrate products.

Volek is a co-founder and former Chief Science Officer of Virta Health, a company that markets a ketogenic diabetes reversal program. He has also served as a scientific advisor to Simply Good Foods, which sells nutritional products, including protein bars, ready-to-drink shakes, meal replacements, and snacks that often emphasize high-protein, low-carbohydrate, low-sugar profiles.

All six helped write the report that shaped the final guidelines. According to the report, the scientists were chosen based on their expertise and “absence of conflicts of interest.”

How Industry Shaped the Message

When new dietary guidelines are written, the government opens a public comment period. Anyone can submit comments, but industries with money, staff, and lawyers tend to dominate. For the 2025 update, more than 31,000 comments were submitted.

Many of the most detailed came from meat, beef, pork, egg, and dairy groups, which pushed back hard against advice to cut back on animal-based foods:

The North American Meat Institute urged USDA and HHS to reject calls to reduce meat consumption, arguing that meat and poultry are nutrient-dense foods. In a public statement, the group said the recommendations were “tone deaf and unrealistic for the 95% of Americans who consume meat.”

The National Cattlemen’s Beef Association objected to replacing beef with beans and lentils, calling the idea unscientific. It wrote that the recommendation was “nonsensical given beef’s proven nutritional value.”

The Beef Checkoff, a producer-funded program, also opposed replacing red meat with legumes, arguing that beans and lentils are not nutritionally equal to beef.The National Pork Producers Council warned that replacing animal protein with plant protein would widen nutrient gaps and reduce access to essential amino acids.

The National Pork Board echoed that concern, writing, “One ounce of beans does not match one ounce of pork in terms of usable protein.”

The Egg Nutrition Center warned that reducing egg intake could worsen shortages of nutrients like choline and vitamin D, noting that “it is extremely difficult” to meet choline needs without eggs or supplements.

United Egg Producers argued that cutting protein servings could discourage egg consumption and confuse consumers.

The National Milk Producers Federation supported three daily servings of dairy and promoted dairy at all fat levels.

The National Dairy Council said dairy foods are hard to replace and help close nutrient gaps, calling them “an affordable and bioavailable source of nutrition.”

Danone North America urged the government to keep the three-servings-a-day recommendation and warned that cutting dairy could harm bone health.

When the final guidelines were released in 2026, the language closely matched those requests. Americans were told to “prioritize protein foods at every meal” and to include red meat, pork, poultry, seafood, and full-fat dairy as healthy options, with no clear recommendation to eat less red or processed meat, despite that being a key finding of the DGAC report.

How Industry Funded the Protein Push

Behind the scenes, industry groups were also spending heavily to shape public opinion. USDA records show that industry-funded checkoff programs spent tens of millions of dollars on nutrition research, education, and consumer messaging in the years leading up to the new guidelines.

Between 2022 and 2024, the beef checkoff spent more than $23 million on consumer information. From 2022 and 2026, the pork checkoff spent at least $18 million on nutrition and communications programs. Between 2022 and 2024, the egg checkoff spent more than $5 million on nutrition research to inform consumer messaging.

These numbers do not include spending by trade groups, food companies, or lobbyists. But together, they show that the same industries pushing back on the science were also funding the research and messaging shaping how Americans think about protein.

What Happens When We Eat Too Much Protein

If higher protein intake were clearly safer or healthier, the policy shift might make sense. But the biology tells a more mixed story.

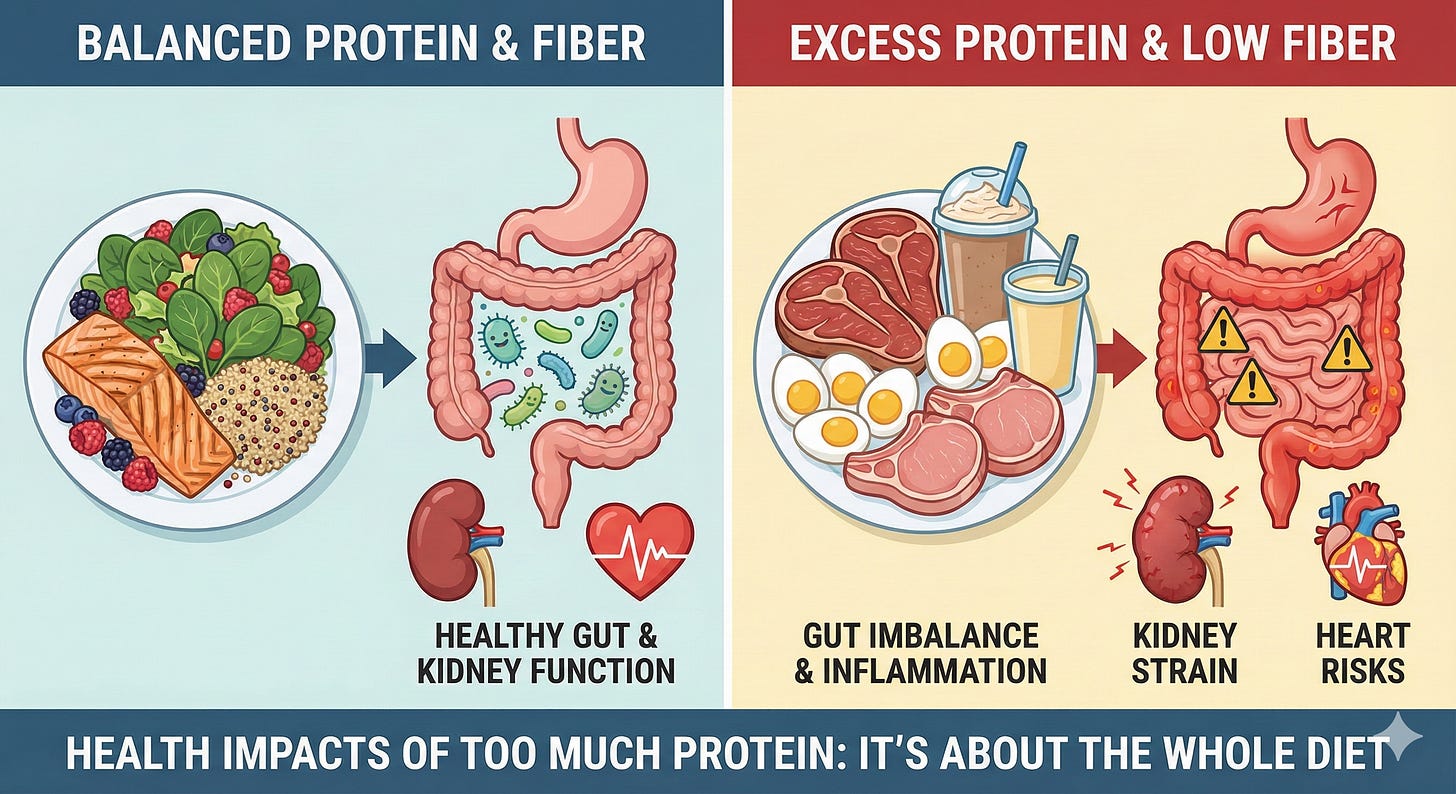

Protein helps build muscle and keeps us full. But too much protein for too long can cause harm.

When we eat more protein than the small intestine can digest, leftover amino acids reach the colon. There, gut bacteria break them down and release chemicals like ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and p-cresol. These chemicals can irritate the gut, increase inflammation, and weaken the gut lining, allowing harmful substances into the bloodstream.

Several studies link this process to gut imbalance, chronic inflammation, and even a higher risk of colorectal cancer and heart disease.

High-protein diets also strain the kidneys, which must remove extra nitrogen waste. For millions of Americans with diabetes, prediabetes, or early kidney disease, this added burden can speed up kidney damage.

Some long-term studies also suggest that very high protein intake may raise heart disease risk, especially in older adults.

The science is still evolving, but one message is clear: more protein isn’t always better, especially when it replaces fiber-rich foods like fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

Policy by Omission

The DGAC scientists found that diets lower in red and processed meat are linked to better heart health. That advice was left out of the final guidelines. Instead, the government now tells Americans to “consume a variety of protein foods from animal sources.”

That wording matters. Federal programs like school lunches, WIC, and SNAP use the Dietary Guidelines to plan meals and buy food. If red meat is framed as a preferred protein, public food programs are likely to buy and serve more of it.

The Double-Edged Sword of Protein

Protein is essential. But too much can cause harm. The new guidelines treat protein as a cure-all, even as evidence shows that long-term excess can damage the gut, kidneys, and heart.

Online, high-protein eating has become a badge of virtue: more is better, less is weak. The government’s message now echoes that same idea. But real nutrition science is more complex.

Health depends on balance, not just how much protein we eat, but what we stop eating when protein crowds everything else out.

The evidence may still be developing, but one lesson is already clear: a healthy diet looks less like a protein shake and more like a plate with room for plants.

Special thanks to Julie Wilcox, MS, nutrition and wellness consultant, for research support.