The Air We Breathe May Be Raising Our Risk of Alzheimer’s

Large Medicare study finds association between long-term PM2.5 exposure and increased Alzheimer’s risk.

Beyond the heart and lungs

For years, scientists have warned that air pollution damages the lungs and strains the heart. Now, new research suggests it may also harm something even more personal: our memory.

A new national study published yesterday in PLOS Medicine finds that long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution is associated with a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. The implication is unsettling but important: cleaning up the air may not just prevent asthma attacks and heart disease. It could help protect our brains as we age.

A study of 28 million Americans

The new study, led by researchers at Emory University, followed 27.8 million people age 65 and older on Medicare from 2000 to 2018. During that time, about 3 million were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

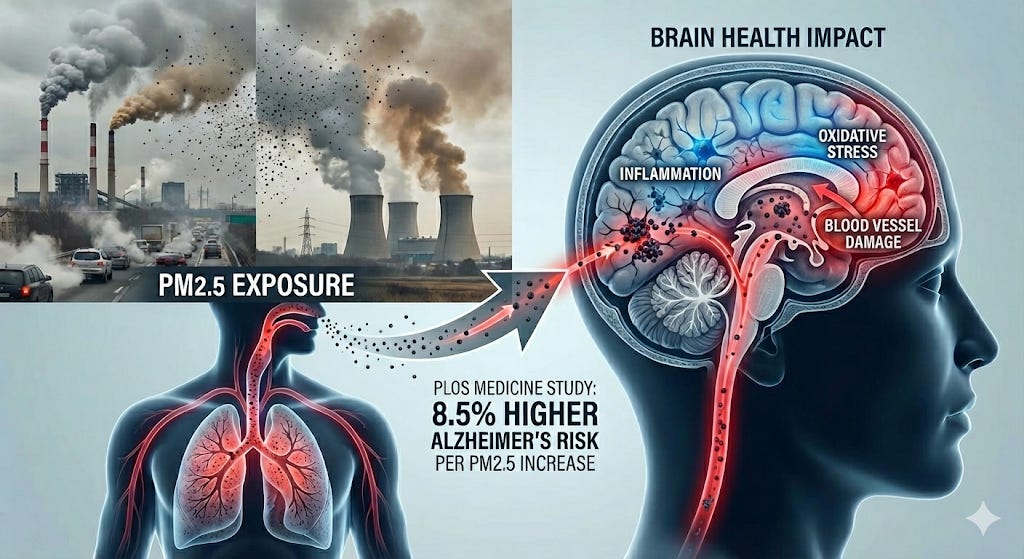

The researchers estimated peoples’ exposure to PM2.5, tiny airborne particles produced by vehicles, power plants, factories, and wildfires. These particles are so small they can travel deep into the lungs and enter the bloodstream.

The result: for every increase in long-term PM2.5 exposure, the risk of developing Alzheimer’s rose by about 8.5%.

An 8.5% increase in risk may sound modest. But across millions of people, that can translate into many more cases.

Does pollution harm the brain directly?

The researchers also asked a crucial question: does air pollution increase Alzheimer’s risk because it causes other health problems first, such as stroke or high blood pressure?

They found that while pollution is linked to stroke, hypertension, and depression, those conditions explained only a small part of the Alzheimer’s risk. In other words, most of the risk wasn’t related to these other health conditions, which suggests pollution may affect the brain more directly.

Scientists have long suspected this might be the case. Research shows that fine particles can trigger inflammation and oxidative stress, processes linked to neurodegeneration.

A growing body of evidence

The new PLOS Medicine study doesn’t stand alone.

A 2021 study of more than 12 million older adults in the U.S. found that long-term exposure to PM2.5 and traffic-related pollution was linked to higher rates of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

Another large U.S. Medicare study reported that each increase in annual PM2.5 exposure was associated with a higher risk of hospital admission for Alzheimer’s and related dementias.

A 2023 study in PNAS found that specific components of PM2.5 — particularly those from traffic and fossil fuel combustion — were strongly linked to dementia risk.

And in 2025, an autopsy-based study found that higher PM2.5 exposure was associated with more severe Alzheimer’s-related brain changes.

Together, these findings suggest that air pollution may not just be associated with dementia. It may be biologically involved in the disease process.

Implications for an aging population

More than 6 million Americans are currently living with Alzheimer’s disease, a number expected to rise sharply in coming decades.

While new drugs may slow disease progression in some patients, they do not cure Alzheimer’s.

Prevention, therefore, becomes critical.

Air quality regulations have already been shown to reduce cardiovascular and respiratory deaths.

If pollution also contributes to dementia risk, then environmental policy may double as brain health policy.

What we still don’t know

The Medicare study relies on health records and pollution estimates based on where people lived. It cannot prove cause and effect. Individual exposure may vary. Genetics, lifestyle, and socioeconomic factors also play roles.

But the consistency across large, independent studies strengthens the case that the relationship is real.

The next frontier of research will examine:

Whether reducing pollution lowers dementia risk

Which pollution sources are most harmful

How early-life exposure affects later cognitive decline

Framing Alzheimer’s risk beyond genetics

We often think of Alzheimer’s as a disease of aging or genetics — something that happens to us. But mounting evidence suggests that our environment may also shape our brain health over decades.