Rich People Live Longer. A Super Bowl Ad Says So, But Leaves Out Why.

The ad is right about the gap. But is it right about what causes it or how to close it?

The Health-Wealth Gap Is Real

Opening with a piano riff and imagery meant to evoke HBO’s Succession, the Hims & Hers’ Super Bowl ad opens with a blunt claim: “Rich people live longer.” The commercial argues that wealth buys not just comfort but time, and pitches on-demand telehealth, lab testing, and “early cancer detection through a simple blood test” as a way to narrow what it calls the country’s “health gap.”

And, yes, rich people do on average live longer than poor people. A landmark 2016 JAMA study found that at age 40, men in the top 1% of the income distribution lived nearly 15 years longer than men in the bottom 1%, and women in the top 1% lived about 10 years longer than women in the bottom 1%. The research also showed that from 2001 to 2014, life expectancy rose substantially for higher-income Americans, while it changed little for those at the lowest income levels.

Medical care matters for diagnosing and managing disease. But decades of health research show that most of the gap in life expectancy reflects social and economic conditions — like safer housing, less hazardous work, more stable access to nutritious food, and lower exposure to chronic stress — not new or more medical tests or tools.

U.S. Investment in Prevention Is Small

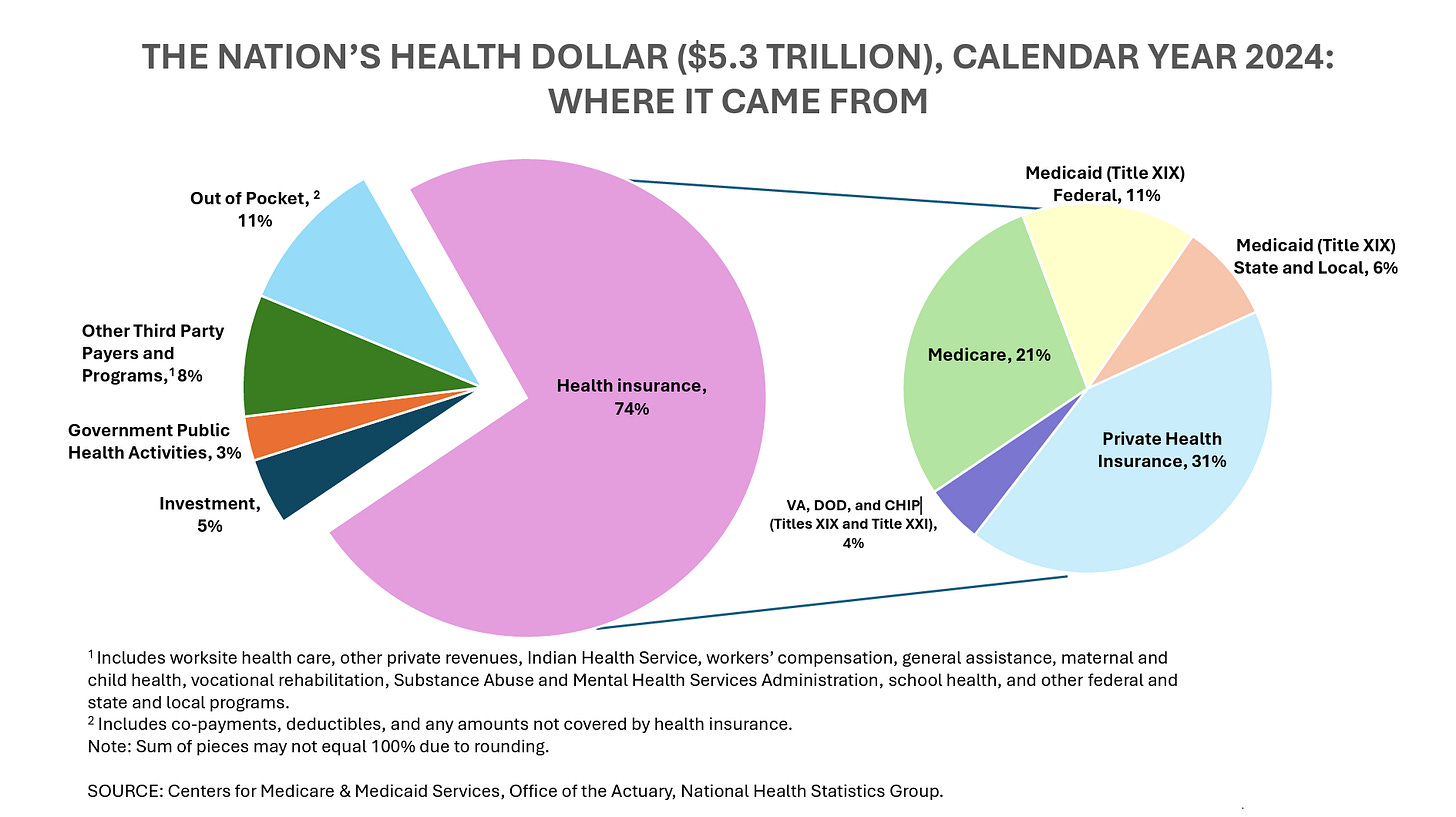

If prevention is the goal, the spending picture is stark. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, U.S. health spending reached about $5.3 trillion in 2024. Only about 3% of that spending went to government public health activities such as disease prevention, health monitoring, and safety programs. Primary care accounted for another 4% of total U.S. health spending.

Far more U.S. health dollars go to specialty care, hospitals, and procedures — the biggest drivers of increasing health costs — than to the services most closely tied to preventing disease.

Primary Care Scarcity

Access to primary care remains uneven across the country. About 20% of Americans live in a primary care Health Professional Shortage Area, meaning there are not enough clinicians to meet local needs. Nearly 1 in 3 Americans lack access to a usual source of primary care because there aren’t enough providers in their communities.

When primary care capacity is limited, prevention can feel elusive. Routine screenings, chronic disease management, and care coordination all thrive in an ongoing clinician-patient relationship, something that many Americans struggle to establish.

Telehealth: Convenience, Not a Fix

Gaps in public health and primary care have helped create demand for telehealth services, which allow people to get some care, like prescription refills, follow-up visits, and mental health support, without traveling to a clinic. But telehealth cannot take the place of public health programs or long-term relationships with primary care providers.

Public health agencies exist to spot danger early, stop disease from spreading, and turn science into practical guidance that keeps people and communities alive. Primary care often involves physical exams, ongoing management of chronic conditions, preventive screenings that require in-person care, and coordination of care.

Telehealth is best for services that do not require physical exams or procedures, and it’s usually added on to in-person care rather than a replacement it. Many older adults, people in rural areas, and lower-income patients face barriers such as limited broadband access or lack of devices, making telehealth harder for them to use effectively.

Evidence versus Marketing

In recent years, companies like Hims & Hers have expanded their offerings to include online lab testing and early intervention services that are marketed as “preventive” or even “longevity” care. Many of these tests — such as cholesterol panels, blood sugar (HbA1C), and hormone levels — are the same routine labs that primary care clinicians order. The difference lies in marketing and framing: such tests are rebranded as “biomarkers,” sold directly to consumers, and positioned as “optimization” tools rather than as tests ordered based on risk, to evaluate symptoms, or to help manage disease.

That shift has potential downsides. Blood-based early detection tests — such as multi-cancer screening panels — have generated significant interest, but they do not replace science-based cancer screenings that require in-person care and follow-up, including Pap smears and HPV testing for cervical cancer; mammograms and ultrasounds for breast cancer; and colonoscopies for colorectal cancer.

Evidence also shows that effective screening depends on the entire continuum of care: identification, follow-up, diagnosis, and treatment coordination.

More testing can also carry harms: false positives, unnecessary procedures, anxiety, and overdiagnosis. That’s why guidelines from bodies like the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force have considered both benefits and harms when recommending screening.

Why the Longevity Message Resonates, and What It Leaves Out

The Hims & Hers ad taps into a broader narrative: the idea that individuals can buy their way to better health using tools and products. Convenience, access, customer service, autonomy, and empathy also matter. But evidence shows that narrowing the longevity gap depends more on enduring social and economic conditions and adequate primary care than on consumer access to tests and treatments.

Hims & Hers argues that the current system has “kept high-quality, preventive healthcare behind a velvet rope.” While Hims & Hers advertises relatively low monthly prices, the typical customer spends several hundred dollars over time. A cheap-sounding subscription can add up to far more out-of-pocket and still provide less value than a primary care visit.

Meanwhile, KFF polling shows that for many Americans, even modest recurring health costs are out of reach: about 4 in 10 adults report having medical or dental debt, underscoring how a monthly subscription model is likely to be most accessible to higher-income patients.