Fact Check: Does Saturated Fat Really Cause Heart Disease?

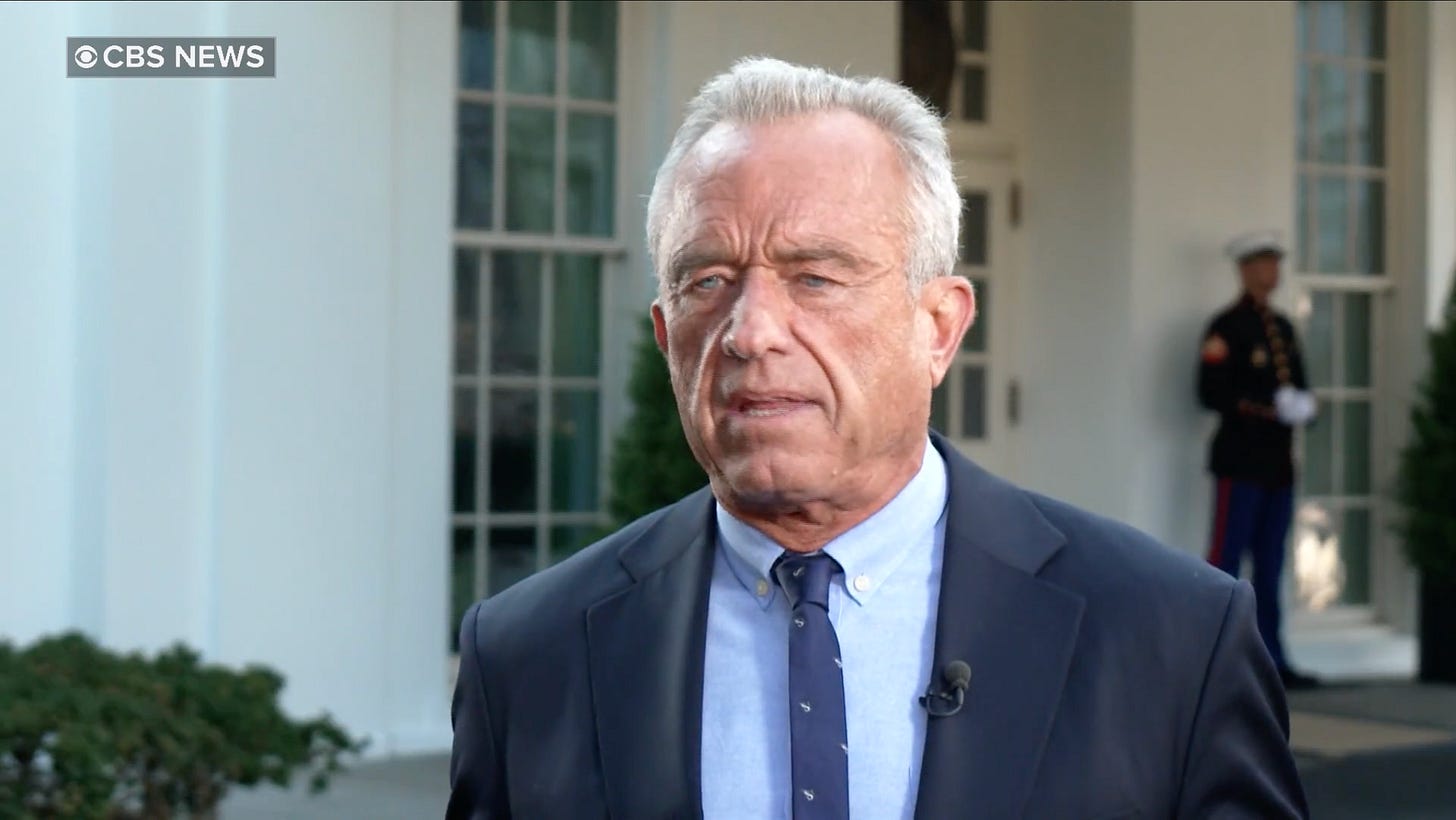

“The problem is that there is no good evidence that saturated fats drive cardiac disease. That is a dogma that was based on a 1960 study that has been completely debunked.”

— HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Kennedy’s statement suggests that scientists were wrong to link saturated fats with heart disease, an idea he says comes from outdated or false research. But what does modern science actually say?

What Are Saturated Fats, Anyway?

Saturated fats are a type of fat found primarily in animal products such as red meat, butter, cheese, and whole milk, as well as in tropical oils such as coconut and palm oil. They are called “saturated” because their chemical structures are filled with hydrogen atoms, which makes them solid at room temperature.

By contrast, unsaturated fats — found in foods like nuts, olive oil, and avocados — contain one or more double bonds between carbon atoms, which creates bends in their structure and keeps them liquid at room temperature.

The American Heart Association (AHA) explains that consuming excessive saturated fat tends to raise low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, the so-called “bad” cholesterol, in the bloodstream. High LDL levels can lead to plaque buildup inside arteries, which narrows them and increases the risk of heart attack and stroke.

In other words, saturated fats don’t directly “cause” a heart attack, but they set off biological changes that make one more likely over time.

What the Strongest Evidence Shows

1. Controlled Trials Show Measurable Benefits from Cutting Saturated Fat

The most direct evidence about cause and effect comes from randomized controlled trials, where participants are randomly assigned to different diets.

According to a 2017 American Heart Association Presidential Advisory, people who replaced saturated fats with polyunsaturated vegetable oils saw about a 30% reduction in cardiovascular disease events, including heart attacks — an effect comparable to taking statin medications.

That means cutting back on saturated fat and replacing it with healthier fats can make a meaningful difference in real-world heart outcomes.

2. Systematic Reviews Back It Up

The Cochrane Collaboration, an independent network that evaluates medical evidence, published a major systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 randomized studies involving more than 56,000 participants.

The review concluded that reducing saturated fat intake for at least two years lowered the risk of combined cardiovascular events by about 17%.

That benefit came with important caveats. The Cochrane authors rated the evidence as “moderate certainty” because the trials were highly variable in quality and design. Some studies dated back to the 1960s and relied on self-reported diets, which are prone to error. Participants weren’t blinded — an unavoidable limitation in food studies — and their diets often differed in what replaced saturated fats. When those fats were swapped for polyunsaturated fats, risk dropped. When they replaced saturated fats with refined carbohydrates (like sugar or white flour), the benefit disappeared; this is what many Americans have done over the last couple of decades. The review’s authors also noted that long-term dietary trials are difficult to control and expensive to run, so adherence and precision inevitably vary. (Note that systematic reviews have their weaknesses, as I explain here.)

Even with those weaknesses, the pattern across studies was clear: lowering saturated fat and replacing it with unsaturated fat modestly but consistently reduced cardiovascular risk.

In other words, what you substitute matters just as much as what you reduce.

3. Long-Term Studies Show Consistent Links

Beyond clinical trials, prospective cohort studies, which follow large groups of people over years, have consistently shown that higher intakes of saturated fat are associated with a greater risk of coronary heart disease.

In one analysis of more than 115,000 adults, researchers found that people who replaced 5% of their daily calories from saturated fat with unsaturated fat reduced their risk of coronary heart disease by 25%.

Why Is There Still a Debate?

Nutrition science is complicated and notoriously hard to do well. Not every study produces identical results because diet, genetics, and lifestyle vary widely among populations.

Most nutrition studies can’t prove cause and effect. To show that one nutrient directly causes disease, scientists would need to control every other variable — exercise, stress, sleep, income, genetics, and countless habits — something that’s almost impossible outside a laboratory.

In medicine, the double-blind randomized controlled trial (RCT) is considered the gold standard for testing cause and effect. In this kind of study, participants are randomly divided into groups: one receives the active treatment, and another gets a placebo. Crucially, neither the participants nor the researchers know who is in which group until the study ends. This “double blinding” prevents bias: no one can consciously or unconsciously influence the results. It’s how scientists know that a pill or vaccine truly works — not just because people think it does.

But food isn’t a pill. You can’t disguise butter as olive oil for six months, and you can’t keep people in a lab 24 hours a day to monitor every bite they take. A rigorous, double-blind diet trial would require feeding participants every meal for months or even years, precisely measuring nutrients, and repeatedly checking blood, weight, and cholesterol levels. That kind of control is astronomically expensive and nearly impossible to sustain in real life. People travel, eat out, skip meals, and misreport what they ate, and you can’t blind them to whether their dinner tastes like steak or tofu.

Because of these real-world limits, researchers rely mostly on observational studies, where participants self-report their diets and are followed for years to see who develops disease. Those studies are excellent at spotting patterns and associations, but they can’t prove causation, because so many factors — genetics, exercise, income, or even how carefully people fill out food questionnaires — can cloud the picture.

These challenges explain why some recent meta-analyses have found weaker or inconsistent links between saturated fat and heart disease. It’s not that the connection isn’t real; it’s that it’s hard to measure precisely when human behavior, biology, and diet interact in so many ways.

Even so, when multiple lines of evidence — lab experiments, clinical trials, and long-term population studies — all point in the same direction, scientists view the overall conclusion as strong. And leading public health authorities, including the AHA and the World Health Organization (WHO), still agree: saturated fat should make up less than 10 percent of total daily calories, ideally replaced with healthier unsaturated fats.

What About the “1960 Study”?

Kennedy’s claim that this “dogma” came from a single 1960s study is misleading. Early research, including the famous “Seven Countries Study” led by Ancel Keys, helped spark interest in diet and heart disease. However, modern recommendations are not based on a single old study. They come from dozens of randomized trials, systematic reviews, and mechanistic studies conducted over the past six decades.

In fact, another Cochrane review reaffirmed that the most rigorous evidence continues to support reducing saturated fat intake to reduce cardiovascular events, particularly among individuals at high risk.

The Bottom Line

Science has evolved, but it hasn’t been “debunked.”

Saturated fats raise LDL (“bad”) cholesterol, which contributes to the buildup of plaque in arteries.

Replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats, like those from olive oil, nuts, or fish, lowers the risk of heart disease.

Replacing saturated fats with refined carbohydrates, like sugar or white bread, does not help and can even make things worse.

While there’s room for nuance in how much saturated fat any one person can safely eat, the overwhelming weight of scientific evidence shows that high saturated fat intake increases cardiovascular risk.

When RFK Jr. claims there is “no good evidence” that saturated fats drive heart disease, that statement does not align with decades of data from the world’s leading medical researchers.

Verdict

The claim that there is “no good evidence” linking saturated fat to heart disease is false.

Decades of research — including large randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, and long-term population studies — show that reducing saturated fat and replacing it with unsaturated fats lowers the risk of heart disease. The best clinical evidence shows about a 30% reduction in cardiovascular events, and comprehensive reviews confirm a significant 17% decrease over time.

The biological mechanism is well established: saturated fat raises LDL cholesterol and atherogenic lipoprotein particles, thereby promoting plaque formation in arteries.

While some recent analyses have found weaker associations, these reflect study design limitations, not an absence of evidence. The most rigorous data still show that lowering saturated fat intake, especially when replaced with healthy fats, reduces major cardiovascular events, particularly heart attacks.

Rating: ❌ False

Strong, consistent evidence links saturated fat to higher heart disease risk, and reducing it measurably lowers that risk.