Autism Research Is Changing, And So Is What “Autism” Means

From Autism Spectrum to Subtypes

For decades, scientists have searched for the causes of autism. Some have looked at genetics, others at chemicals, infections, or even what happens in the womb. The result has been confusing: many clues, few clear answers. Now, two new papers show how the field is dividing into two ways of thinking about autism: one very broad and one very specific.

A study in Nature Pediatric Research looked for patterns across hundreds of pregnancies. Meanwhile, a commentary in the New England Journal of Medicine focused on one relatively rare genetic mutation that has symptoms of autism and has a specific treatment. Together, they suggest that “autism” isn’t one single disease. It’s a group of many conditions that affect how the brain develops.

Looking for Patterns in Pregnancy

In the Nature Pediatric Research study, Australian researchers followed more than a thousand mothers and their babies from pregnancy through childhood. They collected detailed information about each mother’s health, diet, medications, and environment. Later, they checked which children were diagnosed with autism.

The scientists found many possible links. Children were more likely to be diagnosed with autism if their mothers had obesity, mental health problems, or used antidepressants called SSRIs or SNRIs during pregnancy. Exposure to cigarette smoke or vinyl flooring also showed weak connections. Mothers who ate diets rich in folate, iron, and magnesium seemed less likely to have children with autism.

The researchers were careful to say that these were associations, not proof of cause and effect. Only 64 of the children in the study were later diagnosed with autism, so the numbers were very small. Missing information was common, and the study didn’t control for many other factors that could explain the results. Scientists call this problem confounding. That means two things can seem linked even though another factor explains both (see below for a more detailed explanation of confounding). For example, mothers who take antidepressants during pregnancy usually do so because they have depression or anxiety, and those conditions themselves may influence a baby’s brain development. Without accounting for that, it can look like the medicine causes autism, when in fact both might be connected to a third factor.

Dr. Charles Nelson, a professor of pediatrics and neuroscience at Harvard Medical School, said he appreciated that the study looked at many possibilities at once. “But the problem is specificity,” he said. “If they’d tested for speech delay or ADHD, they might have found the same results. These factors probably aren’t unique to autism.”

Dr. Nelson also compared the research to earlier worries about Tylenol (acetaminophen) and brain development. “When moms are anxious or depressed, that stress can affect the baby’s serotonin system,” he explained. “Those same moms are also more likely to take SSRIs. So are we seeing a drug effect, a stress effect, or shared family genetics? Probably a mix of all three.”

“Having untreated depression is so much worse for prenatal development than the pharmacology of treating depression,” he said.

Dr. Elizabeth Berry-Kravis, a pediatric neurologist at Rush University, declined to be interviewed about the paper, saying only:

Who can tell what’s real here – many variables that overlap and no correction for multiple comparisons – at best it points out things to investigate better in future studies. You can’t conclude the SSRIs are associated with autism, as it could be that kids with moms with depression are at increased risk for autism based on genetic family propensity to mental health disorders, and they are on SSRIs because they have depression. I don’t think this sorts much out.

Finally, Dr. Andy Shih, the Chief Science Officer at Autism Speaks, said:

While this study does show an association between maternal SSRI/SNRI use during pregnancy and autism diagnosis, it does not establish causation. … A more important question may be why some mothers are taking these medications in the first place. We already know that poor maternal mental and physical health like maternal depression during pregnancy are risk factors for autism. … It’s also important to be careful about how findings like these are communicated. At Autism Speaks, we believe that research on prenatal exposures runs the risk of being miscommunicated in ways that inadvertently blame parents, which is harmful and not supported by the science.

In other words, the study doesn’t give simple answers. What it does offer is a map of possible biological pathways — inflammation, oxidative stress, and how cells make energy — that could link environment and genes.

When One Gene Does Explain A Lot

While the Nature team cast a wide net, the New England Journal of Medicine commentary zoomed in on one tiny corner of the autism world. It focused on FOLR1-related cerebral folate transport deficiency, a rare inherited disorder caused by a faulty gene. The problem blocks folate, a form of vitamin B9, from entering the brain. Children with this defect can have seizures, developmental delays, and symptoms that resemble autism.

In 2025, the Food and Drug Administration updated the drug label for leucovorin (also called folinic acid). The update recognized that leucovorin can treat this specific folate-transport disorder, not autism in general. Still, some public figures twisted the announcement into claims that leucovorin was “a cure for autism” — all forms of autism.

Dr. Richard Frye, president of the Autism Discovery and Research Foundation, has spent much of his career studying leucovorin, a form of folate that appears to help a small group of children with folate transport problems affecting the brain. He cautions that leucovorin is not a cure for autism and should not be used for every child on the spectrum. Dr. Frye has spoken with officials at the Department of Health and Human Services about supporting phase III placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials of leucovorin to treat FOLR1-related cerebral folate transport deficiency, but his research hasn’t been funded.

In the New England Journal of Medicine commentary, Drs. David Goldman and Bruce Chabner wrote: “We believe any future expansion of FDA approval for leucovorin to include autism must be based on evidence from large-scale, well-designed clinical trials.”

Two Ways of Seeing Autism

The two publications highlight a basic split in autism research. One approach studies whole populations to find patterns that might explain why autism develops. The other searches for precise biological mechanisms that can be targeted with medicine. Each method has value, but each also has limits.

Population studies remind us that the environment matters — that prenatal health, nutrition, and stress can shape a developing brain. Mechanistic studies remind us that some children’s symptoms come from specific molecular or genetic causes that we can diagnose and, sometimes, treat.

Dr. Nelson thinks both are necessary, but warns that “autism” is still a catch-all term. “Some kids in these studies might have very low IQs and no language,” he said. “Others might be high-functioning college students. We’re lumping them together under one label, but biologically they’re different.”

Over time, he believes, autism will be divided into smaller, clearer categories. “If you play that out, does that mean in 15 years we won’t have autism anymore? We’ll have a hundred different sub-disorders… they’ll lend themselves to very different treatments,” said Dr. Nelson. Conditions with known biological causes, like the folate-transport disorder, will move into their own buckets. What remains will be the unexplained cases: “autisms” that still defy understanding.

Beyond the Silver Bullet

Both studies carry lessons for scientists and the public. The Australian team’s work reminds us that health before and during pregnancy matters and that complex interactions — between genes, nutrition, and the environment — shape child development. The folate-transport research shows how precise science can lead to targeted treatments.

But both also warn against easy answers. There is no single cause of autism, and no single cure. The best way forward is patience, better-designed studies, and clear communication so that early findings aren’t turned into headlines that mislead families desperate for hope.

What, Again, Is Confounding?

Confounding is when a third factor makes an exposure and an outcome look linked, even if the exposure isn’t actually causing the outcome.

Let’s start with an everyday example: “Do umbrellas cause people to get wet?” After all, this man used an umbrella and still ended up soaked. Common sense, right?

But that’s the classic setup for confounding.

Exposure: Using an umbrella (and wearing a trench coat)

Outcome: Getting wet

Confounder: Bad weather (pouring rain + strong wind gusts)

The confounder (severe weather) is linked to both:

Umbrella use: When it’s pouring and windy, people are much more likely to grab an umbrella + coat.

Getting wet: Pouring rain + wind makes you likely to get soaked regardless.

So if you observe what’s happening in the real world, you’ll see people with umbrellas often look wetter than people without umbrellas; this isn’t because umbrellas make you wet, but because umbrellas are a marker for the real cause: it’s raining hard (and windy).

Why is the man getting wet?

The rain and wind are causing him to get wet.

The umbrella is a response to the rain; it’s not the root cause.

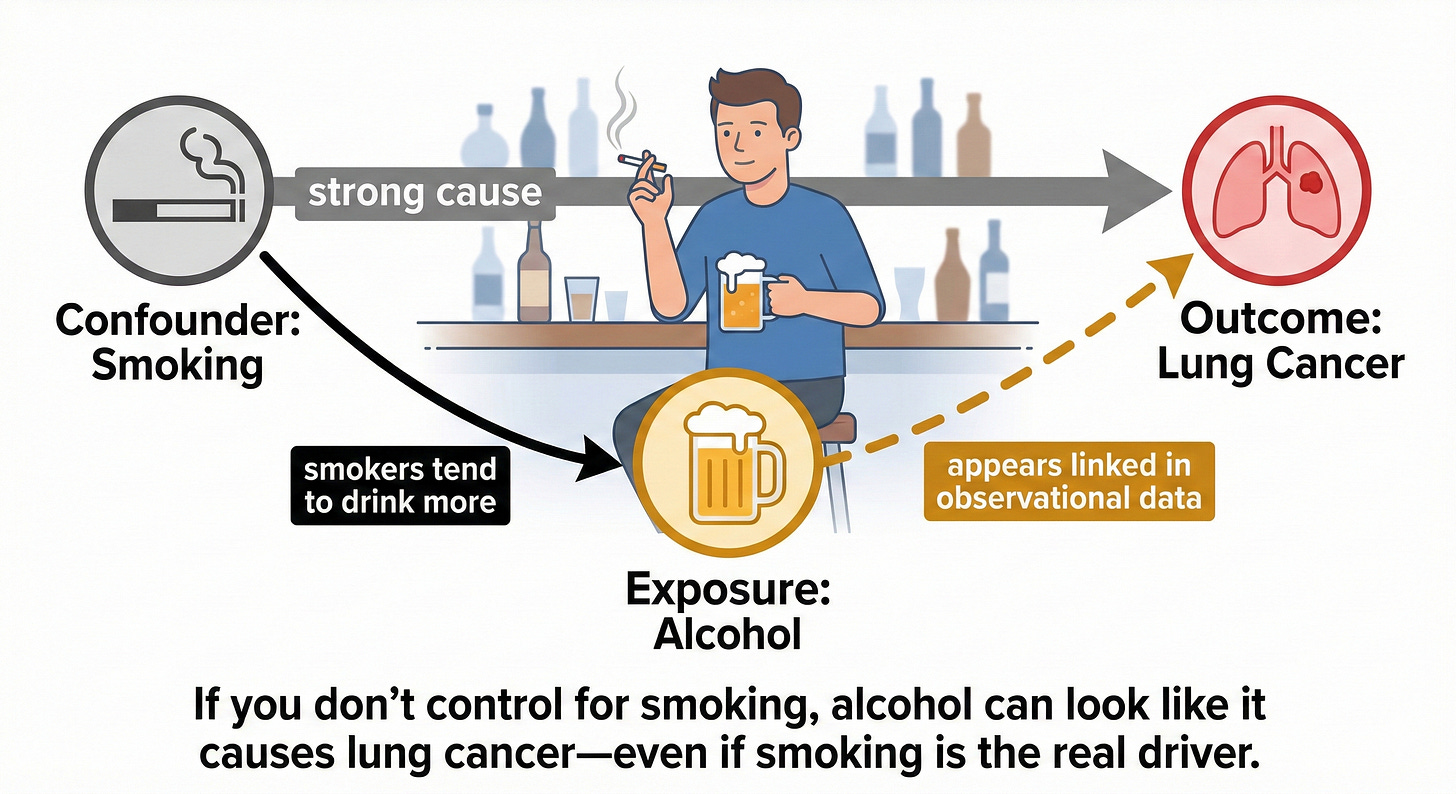

Now let’s look at a classic example from epidemiology textbooks: “Does drinking alcohol cause lung cancer?” People who smoke cigarettes also tend to drink more heavily.

In this example:

Exposure: Alcohol consumption (beer)

Outcome: Lung cancer

Confounder: Smoking (cigarettes)

What’s happening:

Smoking increases lung cancer risk, so smokers are more likely to develop lung cancer than non-smokers.

Smoking is also linked to drinking more alcohol in many populations, so smokers are also more likely to be drinkers (or heavier drinkers).

Because smoking is connected to both the exposure (alcohol) and the outcome (lung cancer), it creates confusion:

When you look at people who drink vs don’t drink, the “drinking group” will likely include more smokers.

Then lung cancer looks more common in drinkers, not necessarily because alcohol caused it, but because smoking was more common among drinkers.

But, if the alcohol-lung cancer link shrinks or disappears after controlling for smoking, that’s the signature of confounding: alcohol was “tagging along” with smoking.

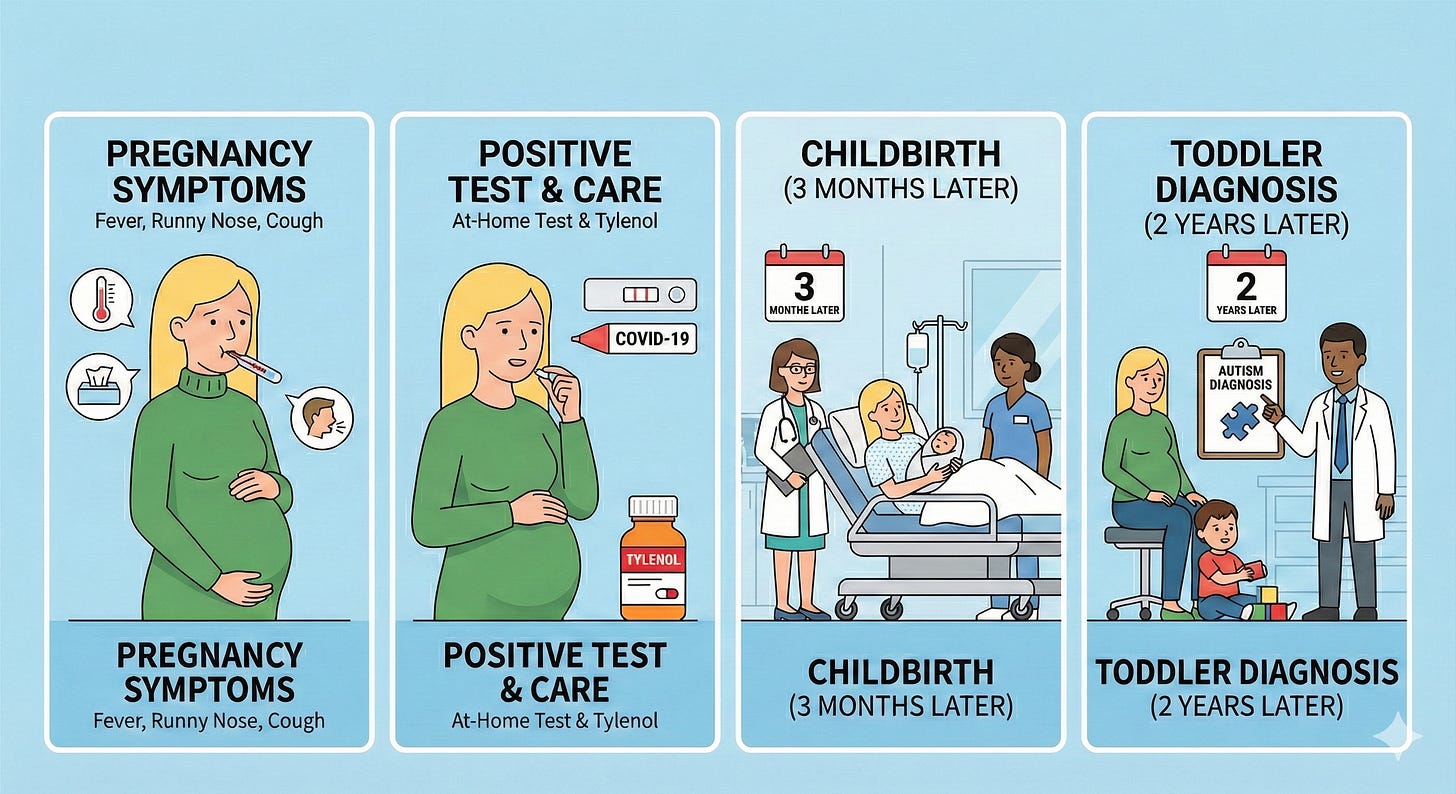

Finally, older studies that found an association between Tylenol (acetaminophen) and autism are another good example of confounding:

In this example:

Exposure: Taking acetaminophen during pregnancy

Outcome: A baby with autism

Confounder: Fever or infection during pregnancy

What’s happening:

For years, researchers noticed that mothers who reported fevers while pregnant were more likely to have children later diagnosed with autism. Because many of those same mothers took acetaminophen to lower the fever, some people assumed the medicine must be the cause.

But fever itself can affect fetal brain development, especially if it lasts for several days or occurs early in pregnancy. The body’s immune response to infection — inflammation, high temperature, and stress hormones — can all influence how neurons grow and connect. In other words, the infection and fever are a real risk factor. Mothers who take acetaminophen are often those who have been sick enough to need it.